Seeking better outcomes for cataract kids

Even in a good health system, children with cataracts sometimes miss out on optimal care, says Auckland University researcher Dr Lisa Hamm.

Dr Hamm is co-author of a study, Phenomenological approach to childhood cataract treatment in New Zealand using semi-structured interviews: how might we improve provision of care, published in the British Medical Journal (BMJ Open), which found some barriers to accessing prompt treatment could be relatively easy to mitigate.

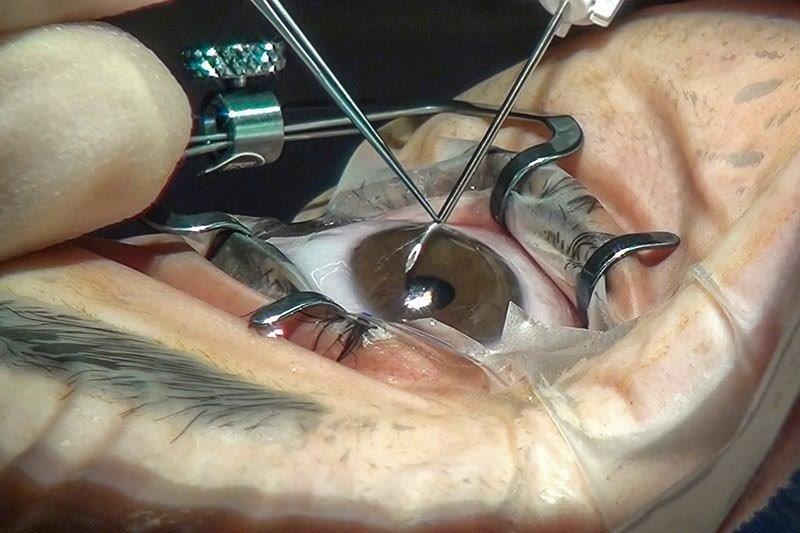

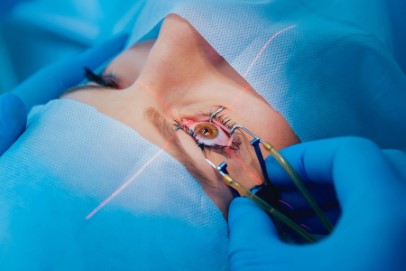

Recommendations resulting from the study include improving screening practices, streamlining referral pathways to specialised paediatric ophthalmologists and improving communication between families and medical staff. It also highlighted the need for better and more creative ways to support families with surgical uptake and post-surgical follow-up. “This requires awareness of family context, including available emotional and practical support… with an emphasis on empathetic, individualised care,” the authors wrote.

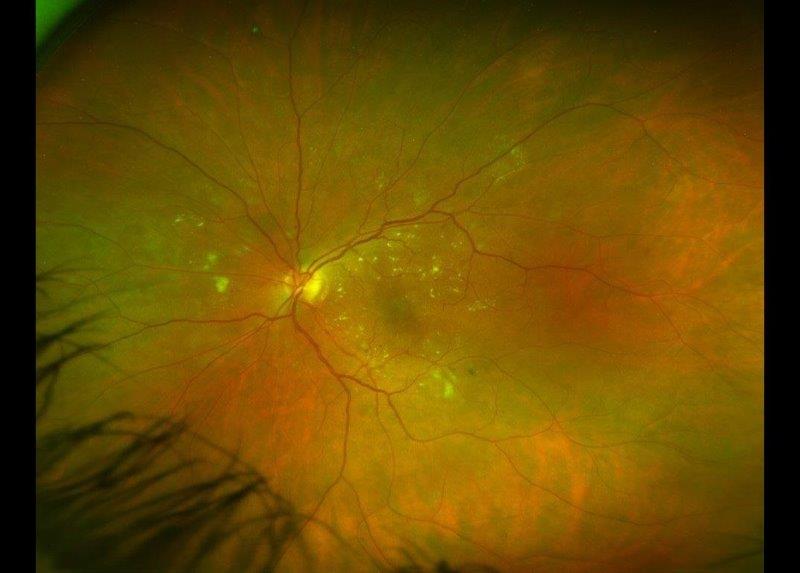

“Children born with cataracts need to access treatment as soon as possible,” says Dr Hamm. “The longer the cataracts prevent visual information from getting to the brain, the poorer the outcome will be.”

Dr Hamm’s study was inspired by the community work she’d done with children born with cataracts in Canada and Tanzania. Despite cataracts being screened for at birth in New Zealand and cataract removal surgery being free, the study found cataract removal was delayed for some children. Delays were related to screening and referral pathways not playing out as they should, a breakdown in communication between families and health care workers and a lack of social support for families to follow through with recommendations.

Adding she’d like to delve deeper into these issues, Dr Hamm was quick to point out that the system in New Zealand was great, but the study was about finding ways to make it even better.

“I'm interested in the impact of cultural beliefs about health on parents’ health-seeking behaviour. I'm currently working with a childhood blindness programme in Uganda, which sees lots of children with delayed access to cataract removal surgery. Some of the strategies they use to address these delays may be useful for vulnerable families in New Zealand. For example, having counselling as a first step after diagnosis and identifying families who may need help arranging transport for surgery. Looking at how we train midwives and primary care workers to implement the screening, and the importance of prompt referrals may also be helpful.

“Primary care specialists wouldn't see cases of childhood cataract very often, so the pressure on these professionals to get it right when they do can be daunting,” she added.