Reflections from an optometric dinosaur

Christchurch optometrist Jonathan Foate completed his DipOpt in 1976, joined Rose & Connor in early 1977 and became a partner in 1980 before making it his own with optometrist wife Michelle. In 2019 he handed the reins to his practice manager son Edward and optometrist daughter Miriam. NZ Optics asked him to reflect on what was and what might be.

By Jonathan Foate

When I embarked upon a DipOpt in 1974, following a BSc at Canterbury, there were just 12 of us. Our lectures were held at 9 Symonds St, Auckland, in an old villa, while our ‘clinics’ were held in the villa next door. In those days, Auckland University’s optometry school came under the direction of the Psyc. Dept, largely because of the relationships that were pivotal in establishing the course in 1965.

A DipOpt required an intermediate year and, once you were accepted onto the course, three ‘professional’ years. This four-year diploma was a great irritation to Auckland Uni as the time and content was inconsistent with a BSc degree, but it was many years before a Bachelor of Optometry degree (BOptom) was formalised.

When the university’s new medical school was built in the late 1970s, the plan was to relocate the optometry school and clinics to the ground floor. This move was promised for our final year but did not happen until years later. Today, optometry is a department in its own right, occupying two whole floors of the more aptly called Faculty of Medical and Health Science.

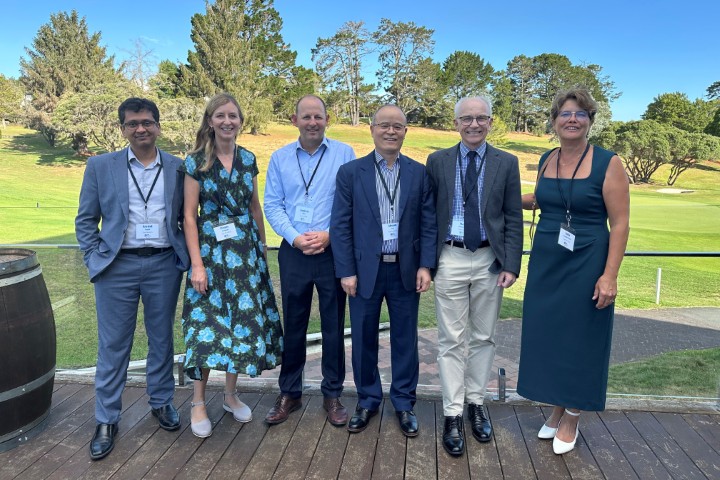

Optometrists Jonathan and Michelle Foate in 2001, outside their original Victoria Street premises, which fell victim to the Christchurch earthquakes

Practices, technology of the past

When I graduated, the only diagnostic pharmaceutical agents (DPAs) available to optometrists were topical anaesthetics. Tonometry was Goldmann, direct ophthalmoscopy and retinoscopy were routine, and we assessed visual fields on a Bjerrum screen. Non-contact tonometry, autorefractors, fundus cameras and automated field screeners had yet to be invented. Information technology was nonexistent: there were no PCs, no internet and no email or cell phones. The appointment book was literally that and referral letters and all correspondence were typed and posted. I recall installing our first fax machine. What an innovation!

Contact lens practice in the 1970s involved hard lenses of poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA), a fairly stiff plastic, and thick, lathe-cut, daily wear soft lenses made of hydroxyethylmethacrylate (HEMA), a soft, water-containing plastic polymer. A lot of effort went into managing corneal oedema, spectacle blur was commonplace and soft lens disinfection systems were heat or hydrogen peroxide. But it was an age of development. Contact lens conferences were exciting and entertaining, with the rapid development of lens designs followed by an array of more comfortable rigid gas-permeable (RGP) materials with ever-improving oxygen permeability and complicated surface treatments. Soft lenses became thinner and with higher water content. There was a short burst of enthusiasm for ‘continuous wear’ but eventually disposables dominated the contact lens sector. Regrettably, disposable lenses have become a commodity item today, with manufacturers often attempting to bypass eye-care practitioners and the eye health checks and advice they provide, with direct sales to consumers online.

In the past, optometry practices were owned by sole practitioners or partnerships; the law did not permit company structures. Shop windows were not permitted. In fact, any frame display visible from outside the practice was frowned upon! As today, most frames were imported but back then brands were subject to import licenses and so effectively rationed. Can you imagine a rep today advising you that your quota of a particular style of frames is 10?

My evolution as an optometrist

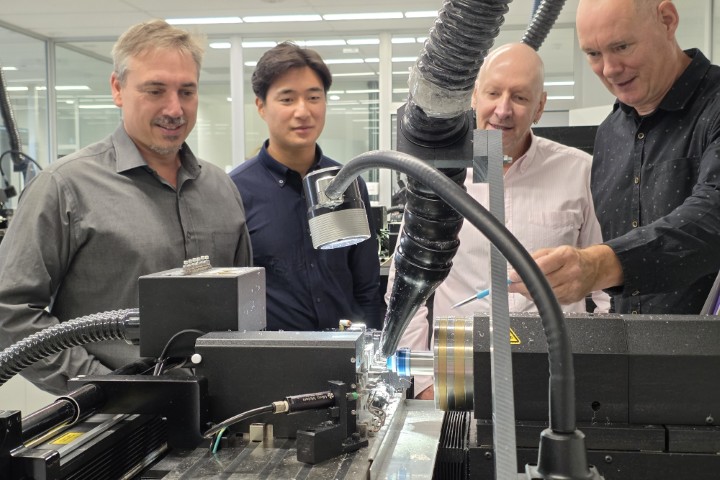

As a new grad, I was fortunate to work with Albert Rose and John Connor in their well-equipped and progressive Hereford Street practice in Christchurch. Our large consulting rooms each had a motorised chair and stand, a refractor head, an internally illuminated letter chart, a Haag-Streit slit lamp and a B&L keratometer. The first new instrument I bought was a radiuscope, which are no longer available; I still have mine. Today we have technology galore: practice management IT systems, software-driven letter charts, autorefractor/keratometer/pacimeter combos, matrix field screeners, fundus cameras, OCTs (optical coherence tomography), a topographer and a portfolio of DPAs and TPAs (therapeutic pharmaceutical agents)!

The original Rose & Connor practice prior to Jonathan Foate joining

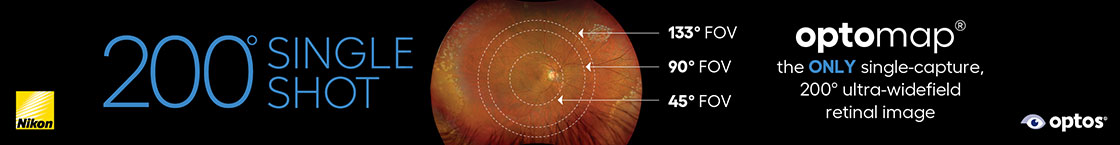

When we bought our first digital fundus camera (probably about 20 years ago), there were conflicting opinions about the image quality provided by the three-megapixel Nikon on the Topcon unit; today your iPhone camera is at least four times as powerful!

On reflection

It has been gratifying to see the scope of optometric practice expand and develop, and the increasingly high level of education of our new graduates. For any new graduate, I have always been of the view that ‘use it or lose it’ is good advice when it comes to their clinical skills. But I continue to have concerns that our young practitioners are not necessarily receiving the mentoring and support they deserve in their early years of practice.

Clinical excellence is important, but optometrists increasingly seem to have been sold the story that their role should be confined to the consulting room and, worse, that dispensing and eyewear technical skills are beneath them. I think the reality is that this facet of our profession is a low priority for today’s optometry lecturers, and it suits the corporate model to remove the optometrist from the sales process.

Patients should and do assume their optometrist is clinically competent and the examination procedures appropriate. But communication skills and everything outside the consulting room are as significant to the patient experience as the examination itself. Optometry is, after all, a relationship business.

One of the most obvious changes during my working life has been the ‘corporatisation’ of healthcare, be it in optometry, dentistry, radiology or audiology. All of the corporate models are supply-chain, sales-driven, profit-focused models of one sort or another, with a view to maximising the return to shareholders. In this model, optometry can become but a small cog, necessary to initiating a sales process. To state the obvious, most of our patients do not have eye disease and their vision needs require skilful refraction coupled with prescribing and dispensing expertise. So it’s regrettable that the practitioner-patient relationship and the fundamentals of providing good patient care seem to be increasingly irrelevant. Optometrists are in danger of losing many of the practical and technical skills so important to providing quality outcomes based on individual patient needs.

Do I have any words of wisdom to end these ramblings? Certainly I do!

They apply to work and personal life: life is a short one-way trip, so make sure you enjoy the journey! Don’t become so focused (pun intended) on big goals and milestones that you overlook often brief, day-to-day happenings – life is a tapestry of little things, don’t miss them; believe me, time slips by very quickly!

All the best, Jonathan Foate