Book review Crashing Through, by Robert Kurson

A world-record-holder for speed in downhill skiing, a CIA analyst, a fundraiser who generated almost US$7 million to produce the world’s first laser turntable for music and the founder of a company that developed Sendero, the first accessible GPS for people who are blind and visually impaired – these are just a handful of Mike May’s accolades. That he achieved them all as a blind man is part of why New York Times best-selling author Robert Kurson made him the subject of his book Crashing Through – The extraordinary true story of the man who dared to see (2006).

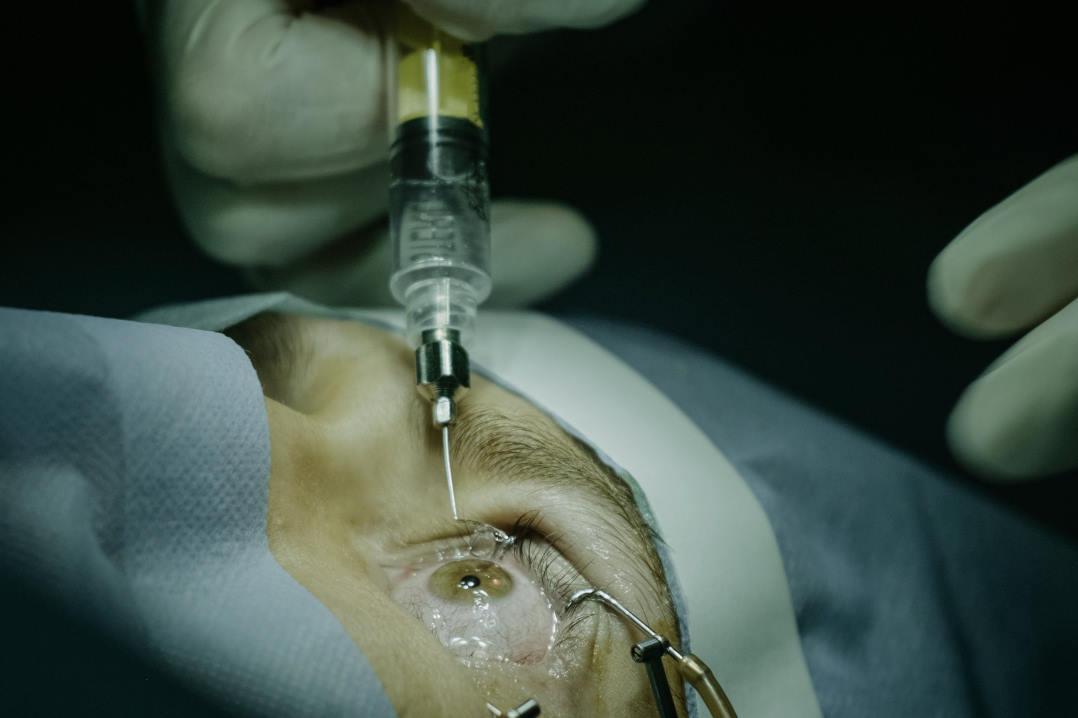

May was blinded at three years old while playing with chemicals he found in the family’s garage. Aged 12, having endured four failed cornea transplants, he accepted his vision would be permanently limited to light perception in one eye. Kurson’s book describes the events leading up to and following the stem cell and corneal transplant that restored vision to May’s viable right eye, 43 years later.

As a boy, May’s determination to enjoy everything available to his sighted peers was both admirable and terrifying. “Mike took tetherballs to the face and dodgeballs to the groin. He bloodied his nose, cracked toes and broke fingers. While running to first base in kickball, he stepped on top of the ball, fell backward, and bashed his head on the pavement. He was unconscious for 20 minutes and rushed to hospital. When he returned to school the next week, he played again.” May told Kurson he would rather feel the exhilarating sensation of moving through space and suffer the inevitable injuries than sit safely on the sidelines.

In 2000, May’s ophthalmologist suggested that, since the right eye was likely to be fully functional behind the ruined cornea, a stem cell transplant eye followed by transplantation of a donor cornea could restore May’s sight. He explained that the stem cells would help regenerate the limbal cells lost in May’s accident and provide a healthy ‘bed’ for the donor cornea.

But at 46 years old, May, married with two young boys, said he was quite content and adjusted to life as a blind man. The risks of surgery, the possible disappointment of its failure (including losing what little light perception he already had) and the significant risk of cancer that comes with using ciclosporin drops to suppress graft rejection, all had to be weighed against the possibility of seeing the world again – and his wife and children for the first time. Not only that, May was also a well-known and respected member of the blind community. Would they reject him if he was no longer one of them? What if his impressive achievements suddenly looked run-of-the-mill for a sighted person? In the end, May decided the risks were probably worth it, but admitted the clincher was that he’d never seen a naked woman.

Mike May in 2024. Credit: Facebook

Lights! Camera! Attraction!

Following the surgery and recovery, May experienced colour for the first time in more than four decades, starting with the floor of the corridor outside the doctor’s office. “Look at those shapes! Look at those colours!” How could the people in the waiting room just sit there when such a carpet is happening, he wondered. However, despite a working eye, May’s brain had forgotten how to translate some of the images it was being presented with, particularly if they were static.

Shadows, which could give a clue to the presence of a roadside kerb; being unable to recognise two-dimensional objects (mistaking a painting for a view through a window or thinking the pictogram on a Ladies’ toilet door was a distant woman) and a lack of depth perception (not realising the grey lines on the floor ahead were stairs) were all vocabulary in the “foreign language” May had to relearn. Pictures of animals had to be identified with deduction rather than recognition – May saw a four-legged animal in his son’s book and declared it a cat. “No,” said his son, “It’s an elephant!”

May also discovered sighted social interactions contained cues and codes for which he was unprepared. Eyebrows danced, lips flapped and hands waved around – all of which only distracted him from absorbing the accompanying audio. Without the typical gender clues May was expecting – a woman’s long hair, jewellery and perhaps exposed legs or midriff – a stranger’s gender was often a mystery to him. Having identified an attractive woman on the street, May’s wife would have to remind him that subtly moving the eye towards its target is less likely to get him punched than rotating his head and staring intently.

May has since been the subject of several studies and Kurson has illustrated Crashing Through with some of the test images he has been asked to interpret. Fascinatingly, many optical illusions don’t seem to fool May’s newly awakened visual processing centres.

For the layperson, this book is a compelling, funny and often jaw-dropping biography that challenges assumptions about what vision is and how the brain copes with stimuli it’s forgotten how to interpret. But for a long-term blind patient considering taking May’s path (it’s also available as an audiobook) or a surgeon in a position to pave it, it might just be a vital read.