Ehlers-Danlos syndromes: the matrix revisited

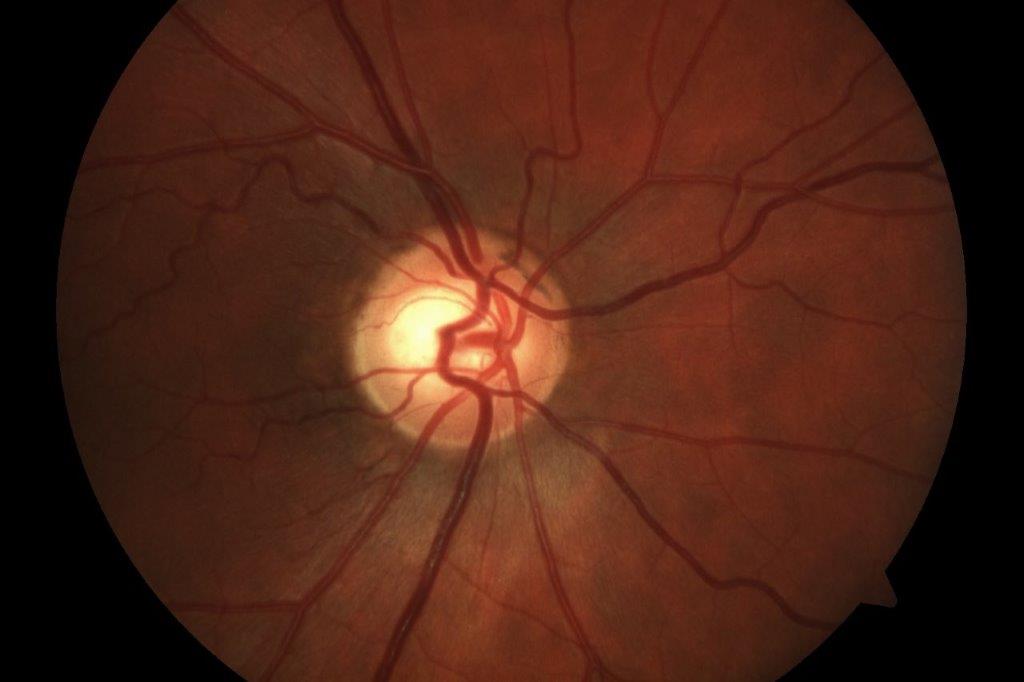

Friday coffee club, two weeks before Christmas, one club member casually described the recent occurrence of a missing circle of vision, filled-in with a metallic scotoma in the inferotemporal quadrant of his left visual field. This precisely described event was monocular and resolved over five minutes. I knew he had a few health issues and I also noticed that his left pupil was smaller than his right. He has mild myopia with regular astigmatism and normal discs and retina, no headache and no inflammatory symptoms. With permission I phoned Greenlane’s eye department and asked if he could be seen.

My friend was full of praise for the attention he received. His medical history included treated, systemic hypertension since the age of 30 and takotsubo cardiomyopathy. The conclusion of the eye department team, which included a neurology consult, was that he had suffered a retinal arteriolar embolism that had moved on without causing lasting damage to his retina – the cardiomyopathy being the most likely culprit. He was prescribed blood thinners and an outpatient CT angiogram was arranged to check on the patency of his carotid arteries.

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy is sometimes called ‘broken heart syndrome’. The name ‘takotsubo’ is taken from distinctive Japanese octopus traps, since hearts with takotsubo cardiomyopathy have a similar shape. In most cases, the cardiomyopathy is temporary but in this gentleman’s case the takotsubo cardiomyopathy resulted in a permanent reduction in ejection fraction to 30%, so his heart contracts poorly and only 30% of the blood in the left ventricle is ejected (a normal ejection fraction is between 55 and 70%). In takotsubo, the cause of the myopathy is non-ischaemic (the coronary blood vessels are not narrowed as with most cardiomyopathies); it may occur suddenly after extreme emotional distress and is usually reversible.

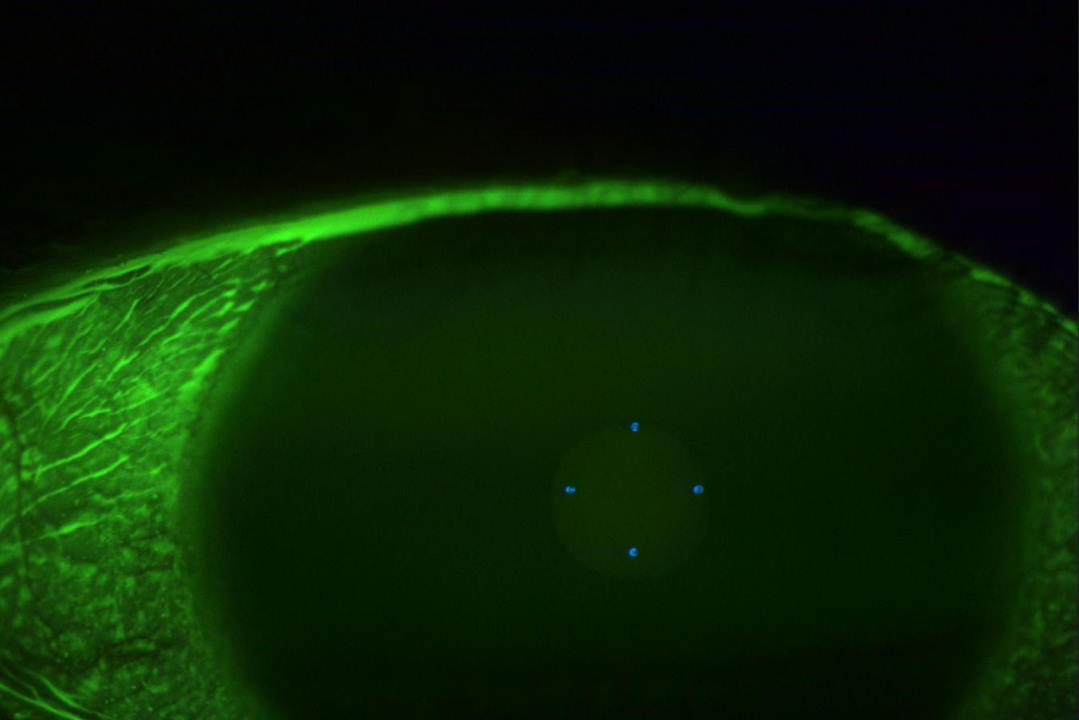

This patient’s CT angiography also returned the surprising finding of bilateral chronic carotid artery dissections in the high internal carotid arteries. This is another turbulence-creating vascular disorder that predisposes to thromboembolism. He had a memory of a terrible headache that put him in bed for three days when he was in his 20s, 40 years earlier; maybe that was when the dissections happened? The carotid arteries were also noted to be chronically enlarged, which probably explains the anisocoria.

Arrows point to patient's cartoid dissections

Ehlers-Danlos syndrome

It is very unusual to have bilateral carotid artery dissections and, at this stage, you are correct to wonder if he has a problem intrinsic to his tissue. The family history is informative: his paternal grandmother died of an aortic dissection at the age of 59 and a paternal aunt died of an aortic dissection at the age of 32. A paternal cousin had a repair of an aortic dissection at the age of 31 and his daughter, who shares her father’s joint hyper-mobility, has been diagnosed with an eating disorder.

Let me interrupt the story at this point to introduce Ehlers-Danlos syndromes (EDS), an uncommon suite of inherited connective tissue diseases. The main clinical hallmarks are hyper-mobility of joints (including dislocation), hyper-elasticity of the skin (stretchy translucent skin), blood vessel fragility (including subconjunctival haemorrhage) and atrophic scarring. For optometrists and ophthalmologists, the most common clinical features of EDS are myopia and dry eye. The show-stopping adverse consequence of EDS is death from the rupture of an arterial aneurysm!

Everyone has or knows someone with double joints or an ugly scar, but deciding whether someone has stretchy translucent skin will not always be clearcut and once the subconjunctival haemorrhage has resolved it’s forgotten. It’s the same problem with myopia and dry eye! Furthermore, there are a number of inherited conditions that share phenotype with EDS, eg. Marfan syndrome, osteogenesis imperfecta and muscular dystrophy.

Ehlers-Danlos has become a popular diagnosis: a recent article in Woman’s Day described the plight of a young woman with EDS who was incorrectly diagnosed with anorexia nervosa – hence my reference to our patient’s daughter, above. The subtype of EDS most likely to be associated with abdominal pain and reduced gut motility is hypermobile EDS, which is also the category of EDS that is least well characterised genetically. These patients can be misdiagnosed with anorexia, but anorexia is common in comparison to hypermobile EDS.

The possibility of an organic cause for an eating disorder opens a small window of hope for families, which explains advocacy around the diagnosis. However, in the case of my friend’s family, given the increasingly strong argument from family history, the possibility that the eating disorder is linked to an inherited connective tissue disease needs re-visiting.

Two Christmases later, my friend suffered a retinal detachment that was repaired successfully (he also has a brother who had a retinal detachment). Subsequently, he developed a cataract, which I removed and replaced with an Alcon Clareon 19.5D T3. Patients with EDS do not have lenticular subluxation – although patients with Marfan syndrome do. I took the precaution of involving an anaesthetist, as sometimes with takotsubo the cardiomyopathy can worsen with the stress of surgery, so his cataract surgery was managed with a propafol infusion.

Risk of arterial rupture

Ehlers-Danlos syndromes encompass a range of genetic disorders that affect the quality of collagen – the body’s structural proteins – and in some cases other elements of the extracellular matrix. There is a wide range of presentations with 13 overlapping clinical categories and 20 genes are now known, so genetic testing enables diagnostic categories to be refined and can add certainty.

The importance of categorising the type of EDS correctly is that ‘vascular EDS’ is associated with arterial rupture at a young age, carotid-cavernous fistula and uterine rupture in the third trimester of pregnancy. If a patient is correctly identified with vascular EDS, surveillance of susceptible vessels can be undertaken within the appropriate subspecialty. The most common clinical type of EDS is classical EDS, which is autosomal dominant, and the major features are generalised joint hypermobility, skin hyperextensibility and easy bruising. This type may also manifest with cavity prolapse (rectal, vaginal or uterine). Other manifestations may include chronic pain, dysautonomia (postural orthostatic hypotension), gastrointestinal dysmobility, mast cell activation and anxiety states.

A recently published (2025) study of 90 million electronic health records from the US concluded that the most common manifestations of EDS in the eye were myopia and dry eye. Also associated were idiopathic intracranial hypertension and carotid-cavernous fistula. The remarkable feature of this case is that the diagnosis has eluded doctors for generations. The genetic test that showed the COL12A1 mutation was self-funded and formal genetic review is still pending. The COL12A1 mutation is associated with myopathic EDS but other non-EDS connective tissue conditions may also be linked.

Ehlers-Danlos syndrome – and the wider context of matrix pathology – is very complex with overlapping diagnostic categories and emerging genetic information. Given our patient’s CT angiography finding, the takusubo diagnosis needs revisiting as it is likely to be unified by the accurate characterising of a connective tissue disorder; hence the referral to genetics services to look for an underlying unifying diagnosis that will be relevant for both this patient and his family.

In summary

This case highlights the complexity of non-inflammatory inherited connective tissue disorders and underscores how easily they can be overlooked. These conditions often present across multiple specialties: cardiology, rheumatology, neurology, gastroenterology, general surgery, psychiatry, paediatrics and ophthalmology. Diagnostic delays are common, with this one spanning nearly a century. This demonstrates the need for an expedited diagnostic pathway, one that integrates genetic testing and a multidisciplinary approach for more timely identification and management.

Further reading

- Forghani et al. Hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome: Diagnostic challenges and the role of genetic testing. Genes (2025) 16(5):530

- Kim et al. Ocular manifestations in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Eye (2025) 39: 1990-1997

- Miklovic et al. Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome. Statpearls NIH

Dr Mark Donaldson is a consultant ophthalmologist at Eye Doctors, Ascot Hospital and Greenlane Clinical Centre in Auckland, specialising in cataract and glaucoma surgery and medical retina. He is also an honorary senior lecturer at the University of Auckland and a trustee of Glaucoma New Zealand.