Gut feelings: microbiome and uveitis

Introduction

Uveitis encompasses a diverse group of inflammatory disorders affecting the uveal tract (iris, ciliary body, choroid) and adjacent structures such as the retina, vitreous, and optic nerve. Its causes include infections, systemic autoimmune diseases, drug reactions, ophthalmologic disorders, masquerade syndromes and idiopathic cases. Predominantly affecting young, working-age adults, uveitis is a leading cause of vision impairment and blindness worldwide.

Current treatment centres on suppressing inflammation to preserve vision, with corticosteroids as the mainstay. However, growing attention is being paid to alternative strategies, including modulation of the microbiome.

The human microbiome, consisting of trillions of microorganisms inhabiting the gut, skin, oral cavity and ocular surface, plays essential roles in digestion, metabolite production, immune system regulation and maintaining mucosal barriers. Disruption of this balance, or dysbiosis, has been linked to autoimmune, metabolic and inflammatory diseases. Emerging evidence suggests a ‘gut-eye axis’ in uveitis, raising the question: could manipulating gut bacteria help manage this chronic eye disease1?

Understanding the microbiome

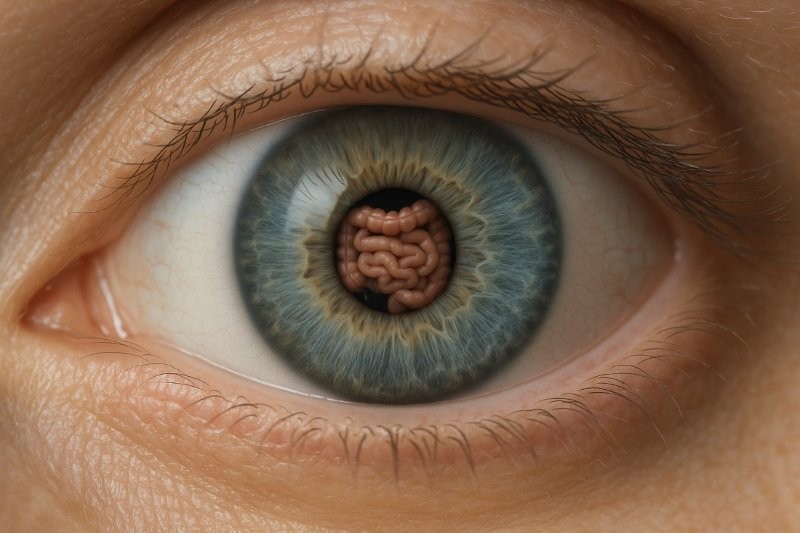

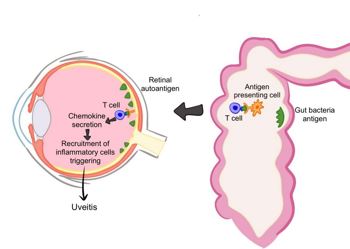

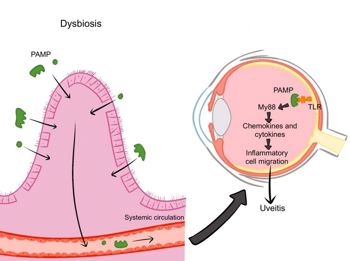

Fig 1. When antigens in the microbiome resemble self-antigens, autoreactive T cells may form and cross into the eye, leading to inflammation. Credit: Samalia et al1

The microbiome’s composition is shaped by host factors (age, genetics, gender), environmental influences (diet, antibiotics), plus external factors such as stress and circadian rhythms, with diet being a primary driver1.

Uveitis arises from a complex interaction of genetic, immune and infectious factors. It occurs when immune tolerance to self-antigens breaks down, leading to autoantibody production, overactivation of Th1 and Th17 cells, and impaired T regulatory (Treg) function. This immune imbalance causes infiltration of T cells and macrophages into the eye. Inflammatory cytokines – especially IL-6, IL-17, IL-23, and TNF-α – play a key role in driving the disease process1.

Gut dysbiosis may contribute to uveitis by being a source of antigens and antigen-specific T cells through1:

- Antigen mimicry – microbial antigens resembling the body’s own self-antigens trigger autoreactive immune responses. In uveitis, gut microbial antigens mayactivate T cells that cross ocular barriers, inducing inflammation. Experimental autoimmune models show that altering gut microbiota can reduce uveitis severity and intestinal TH17 activation.

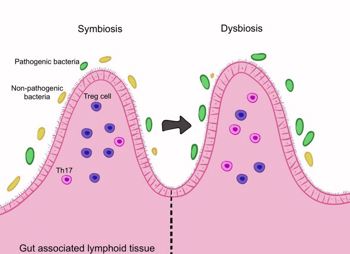

- loss of intestinal-immune system homeostasis – dysbiosis disrupts gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT), increasing pro-inflammatory Th17 cells and reducing Tregs. Gut-derived immune cells have been found in the eyes of experimental autoimmune uveitis (EAU) mice, highlighting the gut-eye axis.

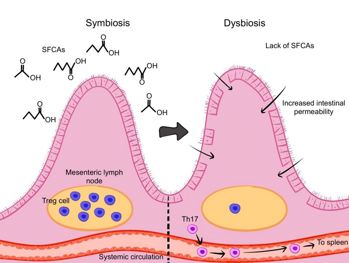

- Microbial metabolites – short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) such as butyrate, propionate and acetate are produced by gut microbiomes and maintain barrier integrity, promote Tregs and limit Th17 migration. SCFA supplementation in EAU models reduces ocular inflammation.

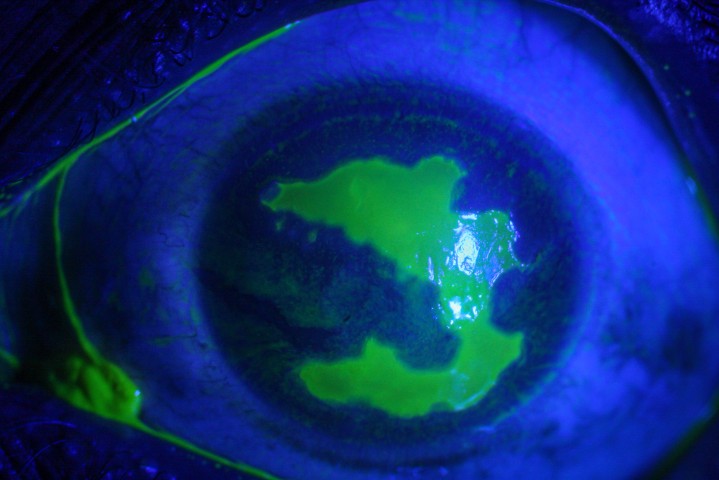

- Barrier dysfunction – dysbiosis compromises the intestinal epithelium, allowing microbial components to enter circulation, activate Toll-like receptors (a class of proteins that are a key part of the body's innate immune system) in ocular tissues and trigger inflammation via MYD88 and NF-κB pathways. Greater gut permeability correlates with earlier and more severe uveitis in animal models.

The microbiome-uveitis link

Fig 2. The gut microbiome maintains the balance between Th17 and Treg cells. Dysbiosis disrupts this balance, promoting inflammation.Credit: Samalia et al1

Gut microbiome – animal studies demonstrate that gut microbiota modulate uveitis onset and severity. Germ-free experimental autoimmune uveitis (EAU) mice show reduced IFN-γ and IL-17 T cells, increased Tregs, and milder disease2. Antibiotics delay and reduce severity, though prolonged use can induce dysbiosis 3. Human studies associate uveitis with reduced bacterial and fungal diversity and an increase in pro-inflammatory species 4. Disease-specific patterns exist: ankylosing spondylitis-associated uveitis shows altered SCFA-producing and arachidonic acid-related species 5, while Behçet’s disease–related uveitis exhibits higher Lachnospiraceae.6

Oral microbiome – Oral dysbiosis may contribute to systemic inflammation and uveitis. Elevated A. actinomycetemcomitans, F. nucleatum, and S. oralis have been reported in idiopathic uveitis7. Behçet’s disease shows increased Veillonella, Gardnerella and other species, highlighting a potential oral-eye axis1,8.

Ocular microbiome – Local dysbiosis may trigger uveitis via antigen-presenting cells and T-cell-mediated inflammation. Elevated Propionibacterium acnes is detected in ocular fluids of uveitis patients and the bacterium has been found in granulomas in patients with ocular sarcoidosis, suggesting microbial contributions to local inflammation1,9.

Implications for diagnosis and treatment

Fig 3. Short-chain fatty acids from the gut microbiota support the intestinal barrier, enhance Treg cells, and limit Th17 cell migration. Credit: Samalia et al1

The microbiome may serve as a biomarker for uveitis risk or flares and offers potential therapeutic avenues1.

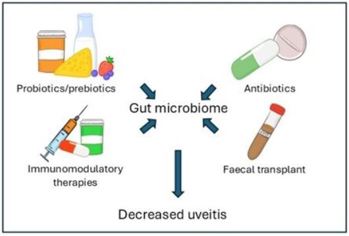

- Probiotics and prebiotics – Probiotic strains such as Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus can restore gut balance, enhance Treg activity and reduce ocular inflammation in EAU models. Prebiotics promote SCFA-producing microbes, supporting Treg differentiation and limiting Th17 activity. Dietary components (prebiotics) can support the growth and activity of SCFA producing microbes. Clinical trials in humans are limited, with optimal strains and dosages still under investigation.

- Faecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) – FMT can restore gut homeostasis. Animal studies show transplantation from healthy wild-type mice reduces ocular inflammation, while FMT from patients with inflammatory disease can worsen uveitis. Human trials are currently lacking.

- Diet-based interventions – Caloric restriction reduces Th1/Th17 proliferation, increases Tregs and alleviates EAU symptoms. Ketogenic diets promote Treg differentiation and restore Th17/Treg balance.

- Antibiotics and microbiome-modulating drugs – Broad-spectrum antibiotics can reduce pro-inflammatory bacteria and ocular inflammation, though overuse risks dysbiosis and resistance. Targeted therapies such as IgA may selectively inhibit harmful bacteria.

- Complementary role with immunosuppressive therapy – DMARDs and biologics not only reduce inflammation but may restore microbial balance. Methotrexate and mycophenolate mofetil enhance Tregs, while adalimumab and infliximab reduce pathogenic bacteria and increase beneficial species, suggesting part of their effect may be microbiome-mediated.

Challenges and controversies

Fig 4. Dysbiosis increases gut permeability, allowing microbial products to reach the eye.TLR activation triggers MYD88-NF- κB signalling, producing cytokines that disrupt ocular barriers and cause uveitis. Credit: Samalia et al4

Establishing causality between microbiome alterations and uveitis is challenging due to microbial diversity, individuality and functional redundancy. Host factors, uveitis heterogeneity and methodological variability complicate interpretation. Next-generation sequencing cannot always distinguish live microbes, low-abundance species, or functional relevance. Evidence largely comes from observational and animal studies, limiting direct clinical translation. Ethical considerations are crucial for interventions like FMT, due to pathogen and immune risks.

Addressing limitations, including small sample sizes, correlation vs. causation, difficulty isolating ocular microbiota, and lack of region-specific data, will be essential for safely integrating microbiome insights into personalised uveitis care.

Conclusion

Fig 5. Modifying the microbiome offers potential treatments for uveitis through approaches such as probiotics, prebiotics and faecal microbiota transplantation. Probiotics and prebiotics aim to restore microbial balance, enhance Treg activity, and strengthen the intestinal barrier. Antibiotics reduce pathogenic bacteria and systemic inflammation, while faecal microbiota transplantation introduces a diverse microbial community to modulate immune function and potentially lessen disease severity

The microbiome is increasingly recognised as a key modulator of immune responses in uveitis, influencing disease onset, severity and treatment outcomes. Microbiome-based diagnostics and therapeutics hold promise for personalised approaches, allowing early detection of imbalances and targeted interventions. However, the relationship is complex and large-scale longitudinal studies are needed to clarify causality and therapeutic potential.

Key message: The microbiome represents a promising new frontier in the understanding and management of uveitis.

References

- Samalia PD, Solanki J, Kam J, et al. From Dysbiosis to Disease: The Microbiome's Influence on Uveitis Pathogenesis. Microorganisms. 2025;13(2):271. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms13020271.

- Heissigerova J, Seidler Stangova P, Klimova A, et al. The Microbiota Determines Susceptibility to Experimental Autoimmune Uveoretinitis. J Immunol Res. 2016;2016:5065703. doi: 10.1155/2016/5065703

- Salvador R, Horai R, Zhang A, et al. Too Much of a Good Thing: Extended Duration of Gut Microbiota Depletion Reverses Protection From Experimental Autoimmune Uveitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2023;64(14):43. doi: 10.1167/iovs.64.14.43.

- Kalyana Chakravarthy S, Jayasudha R, Sai Prashanthi G, et al. Dysbiosis in the Gut Bacterial Microbiome of Patients with Uveitis, an Inflammatory Disease of the Eye. Indian J Microbiol. 2018;58(4):457-469. doi:10.1007/s12088-018-0746-9

- Li M, Liu M, Wang X, et al. Comparison of intestinal microbes and metabolites in active VKH versus acute anterior uveitis associated with ankylosing spondylitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2023:bjo-2023-324125. doi: 10.1136/bjo-2023-324125.

- Yasar Bilge NS, Pérez Brocal V, Kasifoglu T, et al. Intestinal microbiota composition of patients with Behçet's disease: differences between eye, mucocutaneous and vascular involvement. The Rheuma-BIOTA study. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2020;38 Suppl 127(5):60-68.

- Akcalı A, Güven Yılmaz S, Lappin DF, et al. Effect of gingival inflammation on the inflammatory response in patients with idiopathic uveitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2016;43(8):637-45. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12555.

- Sümbüllü M, Kul A, Karataş E, et al. Association between Behçet's disease and apical periodontitis: A cross-sectional study. Dent Med Probl. 2024;61(5):679-685. doi: 10.17219/dmp/163127.

- Li JJ, Yi S, Wei L. Ocular Microbiota and Intraocular Inflammation. Front Immunol. 2020;11:609765. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.609765

Dr Priya Samalia is based in Christchurch as an ophthalmologist with subspecialty training in medical retina and uveitis.

A/Prof Rachael Niederer works as a senior lecturer at the University of Auckland and as an ophthalmologist at Te Whatu Ora Auckland and Auckland Eye, specialising in uveitis and medical retina.