NAAION is nasty

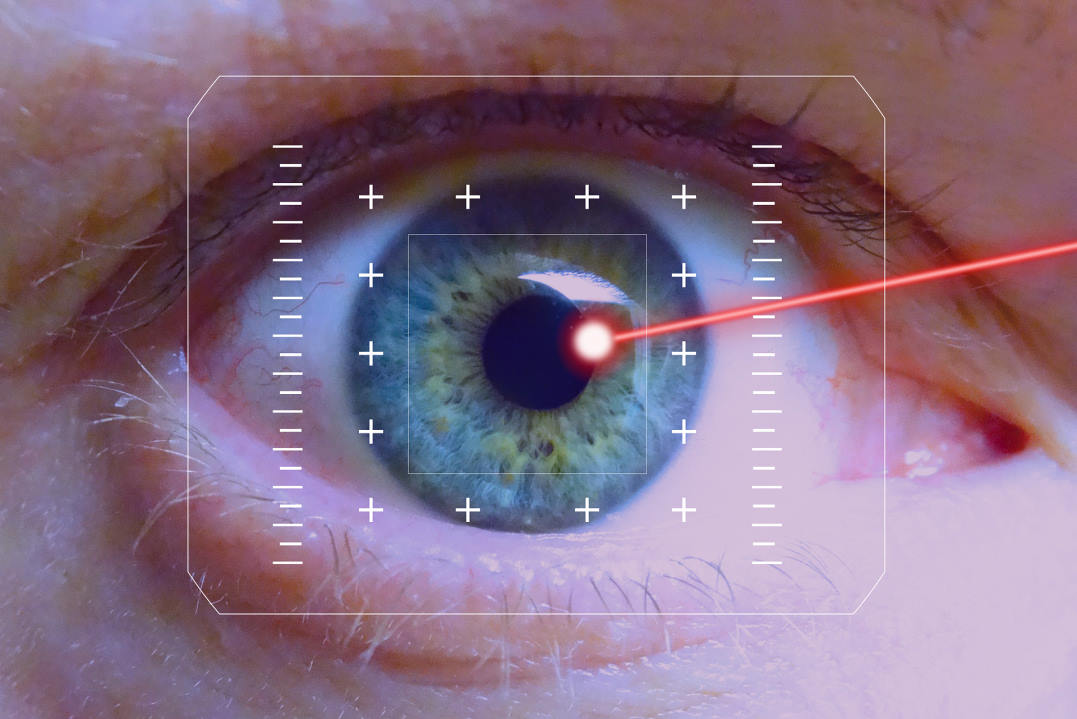

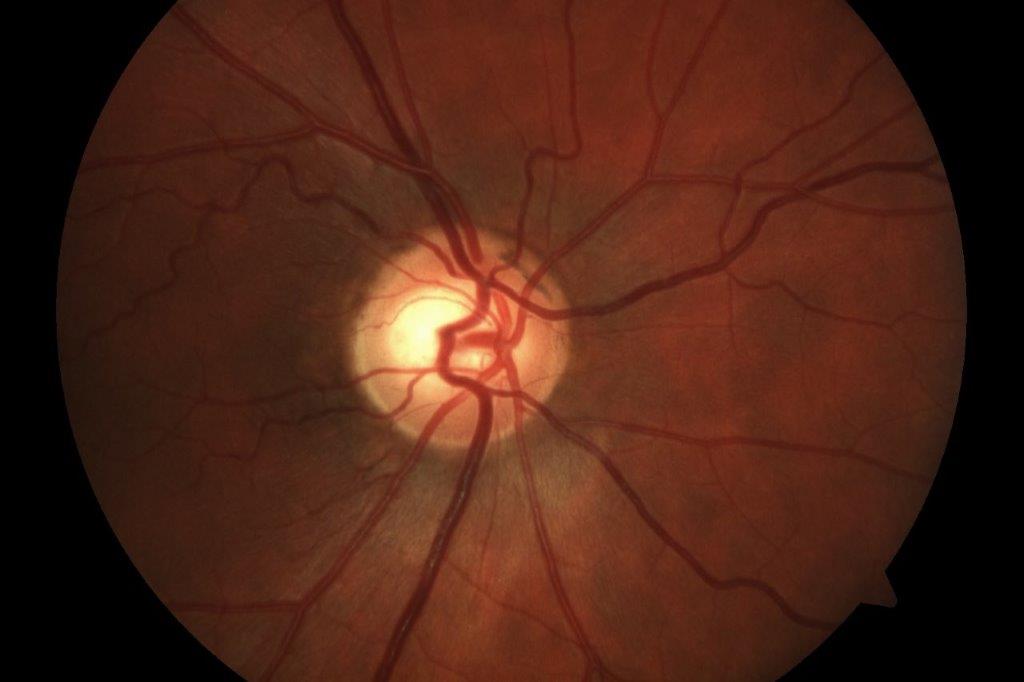

Non-arteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy (NAAION) is a condition where blood flow to the optic nerve is suddenly reduced, causing damage and sudden vision loss, like a stroke affecting the optic nerve.

Although typically described as happening in one eye, in my limited experience of helping patients with this problem, the other eye often soon follows.

It is often linked to factors including high blood pressure, high cholesterol, diabetes, heart or blood vessel disease. It can also be triggered by a sudden drop in blood pressure, especially at night, reducing blood flow to the optic nerve head.

NAAION generally affects people over 50 years old, with a mean onset between 57 and 65 years. It also occurs more frequently in Caucasian populations, with no gender predilection. I have a suspicion that middle-aged type A over-achieving males seem to be more at risk. Recent studies of weight-loss drugs, such as semaglutide (Ozempic or Wegovy) have been associated with a higher risk of NAAION. Other drugs, such as ones commonly prescribed for erectile dysfunction, are also implicated with an increased incidence in males.

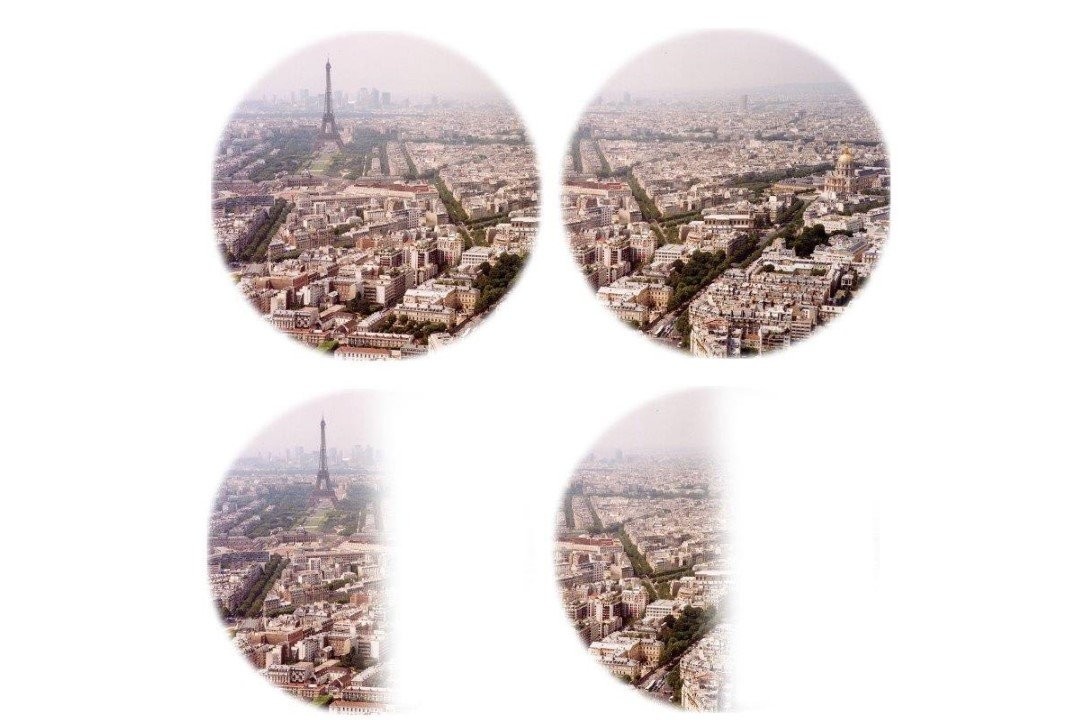

The most common visual-field (VF) defect found in these cases is a combination of a relative inferior altitudinal defect with an absolute inferior nasal defect, though 20–25% of cases show central scotomas. Although a loss of visual acuity (VA) may not be apparent initially, the VF defect is always present at the onset of the disease, so VF testing represents the most important diagnostic test in NAAION1.

Photophobia is also a common complaint, especially in bilateral cases.

Case

Mr T, a 62-year-old male, had experienced vision loss in his left eye in April and right eye in August of the previous year. His general health history included medication for high blood pressure. He was constantly wearing, and was well-adapted to, progressive lenses. His work was primarily computer-based and he was actively involved in his community as a scoutmaster.

His referral to me noted VA (RE) 6/18 and (LE) 6/9 with loss of VF, particularly inferior, but also “some lateral loss”.

Functionally, his main issue was with computer work, where he reported that he could read looking straight ahead at the screen with a slight head tilt upward – as is often required with progressive lenses – but he was unable to see his keyboard unless he looked straight down at his hands, after which he was unable to find his place on the screen.

As anticipated with any inferior VF loss, mobility was an issue, though he had already had assistance with this and was getting more confident using his white cane. He was still troubled by not seeing people coming towards him from either side and had problems judging steps, particularly getting off the bus.

He also mentioned the glare from sunlight and even some indoor lighting caused him problems, but was often unable to use his sunglasses, as changing from his progressive lens spectacles was “another thing to juggle”.

Binocular functional visual fields showed a ring – or rather a square – of total field loss extending to 2.5° inferior to the fixation point and almost 10° superior and to each side (Fig 1). This accounted for the difficulty in mobility, as well as seeing the computer keyboard and other objects unless placed directly in front of him. Binocular near acuity was N5 on a high-contrast chart in average room light. Contrast sensitivity was only slightly reduced.

Fig 1. Binocular functional visual fields

First, do no harm

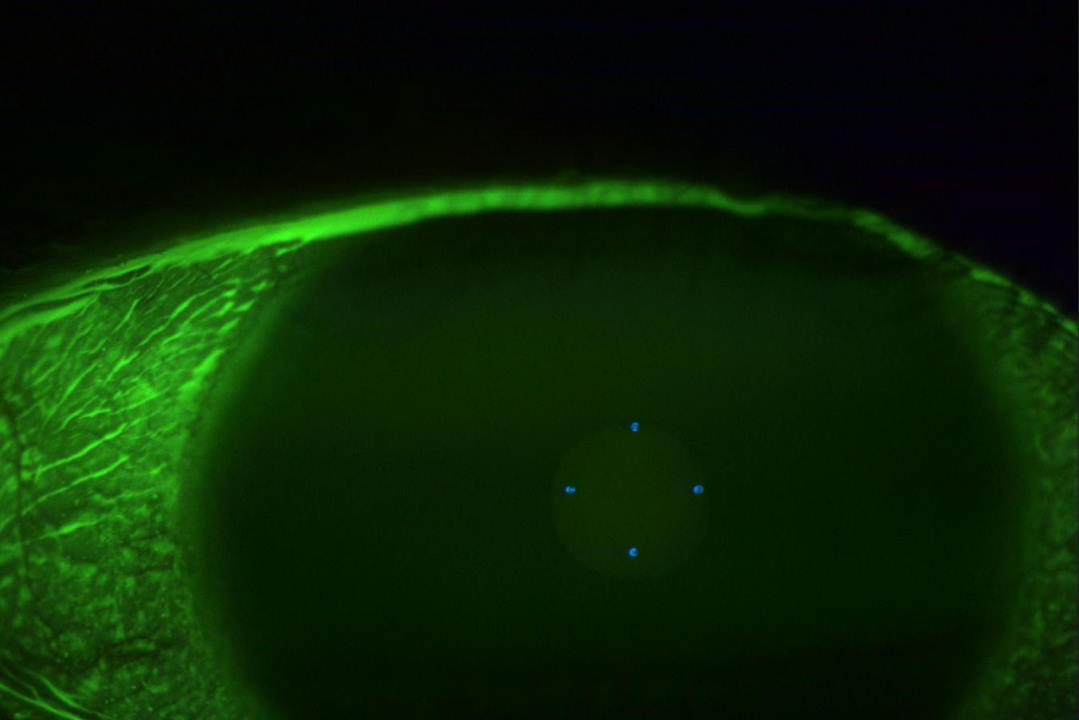

I reminded myself of my obligation to improve this patient’s situation as I decided to use yoked prism base-down in an attempt to lift the image of objects below the line of closer to the centre of the field. I was reluctant to introduce Fresnel prism onto his progressive addition spectacles due to the potential of further compromising his stability while getting used to them; it would also diminish contrast, impeding reading. I decided instead to use a polarised fitover, which gave glare protection, enhanced contrast and could easily be removed as it can hang from a cord around the neck.

A strip of 8D Fresnel prism base-down each eye was fitted to the bottom of each lens inside the fitover. Why 8D? It was the only one I had in the drawer! I also gave him a reverse monocular telescope on trial as a field expander.

At the first review, Mr T reported he was getting used to using the prism for moving around outdoors. He felt he was using his eyes more rather than moving his head and that the prisms helped him to look down more quickly and with less disorientation than when he walks without them. He was, however, struggling with the lack of clarity through the prism.

The reverse telescope was not helpful as a field expander, but the polarised amber fitover was helpful for glare protection and better contrast, though too dark for use inside, he said.

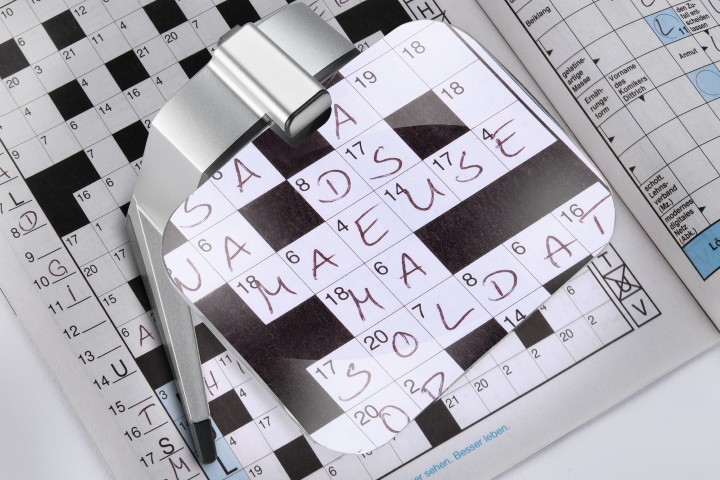

I instructed him in the use of typoscope cards (matt black card with a slot in it) to help him keep his place and awareness of the margins when reading, as well as contrast enhancement. He purchased a book seat (essentially a triangular pyramid of solid foam), which he could turn upside down to elevate his keyboard to the height of his computer screen, so he could see the keys without lowering his gaze as far (Fig 2, above).

I also gave him some visual therapy exercises to build up his saccadic ability for scanning and enhanced peripheral awareness.

On the second review, Mr T reported he “could flick easier to the left than the right”. The exercises were more difficult than he had expected and were not getting any easier. Walking was getting better and he was using the prism more, though steps were still a problem. I observed that the left eye did not appear to be adducting fully.

I cautiously applied a band of 8D base-out for each eye to the outer edges of his progressive lenses. He immediately felt an increased awareness of the periphery. I asked him to try this (carefully) for a week while I ordered some more prisms.

A week later, he reported all was going well. The side prisms were not interfering with his reading or walking as he had to consciously look to the sides to access the prism but could see the small benefit and felt that a stronger prism would give a greater benefit. We discussed getting a second fitover with polarised yellow lenses so that he could use this with the prisms indoors as well as outside.

He then lost the darker fitover, so the decision was made to fit a strip of 15D Fresnel prism base-down 15mm from the bottom bevel of a polarised yellow lens fitover. In addition, a strip of 15D of base-out prism was fitted to the outer temporal edge of each lens of his progressive lenses.

Conclusion

I did not hear from Mr T again. I am assuming that by the time the Fresnel prisms dropped off and got lost, he had improved in his ability to scan in the direction he required to offset his reduced field of vision sufficiently to not need them – a bit like taking the training wheels off the bicycle.

I have learned that with NAAION:

- No two patients will have the same functional loss. There is no one-size-fits-all approach.

- Find out how long it has been since diagnosis and whether there has been any improvement. This may give an indication of whether further improvement is possible.

- Use a large dose of lateral thinking and apply all optical knowledge, resources and skill to find a practical solution. It may not solve the problem, but even a small improvement in how the patient functions may be appreciated.

- Ask the patient what they are finding most difficult as a result of their vision problem. Don’t assume you or their family know what they need.

I always ask myself, “is this patient really motivated to work at this, or is it the family who are wanting to find something to do about their loved one’s problem?”. Is it safe to try things like a prism, which could be a cause – rather than a prevention – of falls? How stable is this person on their feet?

And beware of the family and friends who have already found all the answers via Google and insist they must be tried, projecting their failure to do so onto you!

Reference

- Salvetat ML, Pellegrini F, Spadea L, Salati C, Zeppieri M. Non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (NAAION): a comprehensive overview. Vision (Basel). 2023 Nov 9;7(4):72.

Naomi Meltzer is an optometrist who runs an independent practice specialising in low-vision consultancy. She is a regular contributor to NZ Optics.