Real-world registry boosts dry eye care globally

Despite many available treatments, dry eye disease (DED) remains one of the most underdiagnosed and undertreated conditions in eyecare. Clinical trials to inform treatment development often have strict and narrow criteria and do not always represent the general patient population. Nor do they provide the ability to demonstrate longer-term treatment effects. To bridge this gap, clinical registries are valuable tools for gathering real-world data using a systematic methodology to monitor disease trends, treatment effectiveness, safety and outcomes over a long term1-3.

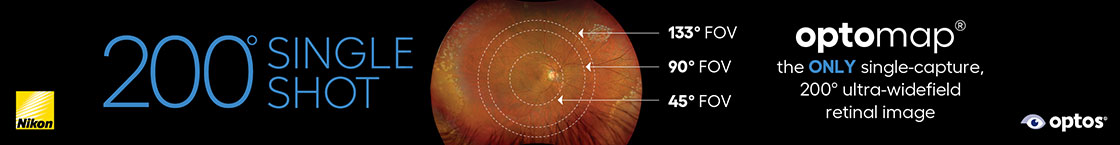

During the last decade, there has been a growth in the number of clinical registries in ophthalmology3; however, little is known about DED from registry outcomes capturing clinical outcomes in patients1. DED clinical registries have the potential to improve patient outcomes by evaluating the effectiveness of different treatments and providing data needed by ophthalmic practitioners for benchmarking1. These data can generate real-world evidence that can guide treatment decisions. The Save Sight Registries (Fig 1), designed to provide maximum data security and anonymity, are easy to use and offer users the opportunity to participate in national and international audits through publications and collaborations2 (Fig 2).

Fig 1. The Save Sight Registries modules focus on the leading causes of visual impairment

The Save Sight Dry Eye Registry (SSDER), established in November 2020, is the world’s first international, interdisciplinary DED registry. It allows clinicians to anonymously contribute to large-scale longitudinal data that relate to multiple aspects of DED diagnosis and management. The SSDER is the second module of the Fight Corneal Blindness! (FCB!) project, following on from the Save Sight Keratoconus Registry module4. It can inform DED natural history and treatment outcomes via data acquisition, which includes demographic details, medical history, prior ocular and systemic medications, clinical signs of DED and patient-reported outcomes using the Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) and Ocular Comfort Index (OCI), plus mental health screening for anxiety and depression using the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4). Information on compliance with treatment and adverse reactions are also obtained.

The registry’s mandatory fields ensure complete and high-quality data entry, with built-in checks and radio buttons for valid data ranges. It typically takes under two minutes to complete the mandatory data field entry for both eyes for first and follow-up visits. Clinicians enter data online via a secure, web-based encrypted system, accessible on various devices and operating systems (eg. Windows PC, Mac OS, iOS, Android) and the registry can be used with a regular internet browser.

The data on diagnostic tests and clinical signs of DED collected by the SSDER are based on the recommendations of the TFOS DEWS II Diagnostic Methodology report and the ‘activity’ and ‘damage’ parameters of the Ocular Surface Disease Scoring System (OSDISS)5,6. Patient data are anonymous within the registry and can be exported as CSV files for further analysis. Practitioners can access only their own patient data, which are anonymised within the system.

Retrospective analysis of the real-world data in the SSDER contributed by ophthalmologists and optometrists from nine practices across Australia, France, Germany, Nepal, Spain and the UK from November 2020 to March 2024 was recently published, co-authored by OSL’s Professor Jennifer Craig, a SSDER Steering Committee member2. The article provided valuable information on DED subtypes, clinical characteristics and treatments in everyday clinical practice based on first visit data for 958 eyes from 479 patients, predominantly female (78.7%) and with an average age of 56 years. Evaporative DED was the most common dry eye subtype (54%), followed by mixed DED (36%) and aqueous-deficient DED (10%), based on clinician judgement. Common comorbidities included meibomian gland dysfunction and previous cataract surgery.

Clinical findings included mean OSDI symptom score of 35.7±16.9 (range 14–100) in 366 patients indicating moderate-to-severe DED symptoms. The mean scores for frequency and intensity of discomfort with the OCI was 31.9±6.1 and 31.4±6.8, respectively, in 202 patients. Symptoms of anxiety and depression were reported by more than one-third of patients. Median tear breakup time and tear meniscus height were 5 seconds (interquartile range 2–8s) and 0.3mm (interquartile range 0.2–0.4mm), respectively. Ocular surface staining was graded with the Oxford scale as none in 37.6% of patients, minimal in 31.7%, mild in 19.8%, moderate in 8.8% and severe in 2.1%.

The most common previously prescribed concomitant treatments, in the order of most to least prescribed, included artificial tear substitutes, anti-inflammatory drops, eyelid warm compresses, biological tear substitutes, eyelid hygiene and diet or nutritional supplements. Other prior treatments included mechanical therapies, such as punctal plugs, and physical treatments, including IPL therapy, eyelid margin debridement, thermal pulsation therapy and manual meibomian gland expression. More than half of the patients self-reported ‘yes’ to compliance with treatment. No adverse events were recorded.

Our findings were consistent with previously published real-world retrospective data of DED patients in the US and Canada7, alerting clinicians of the need to consider the mental health of patients with DED.

The SSDER can be used for benchmarking, as users can compare their patient treatment and outcomes with aggregate data of their peers. For eligible clinicians, continuing professional development points are awarded for data entry from the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Ophthalmologists (RANZCO) and Optometry Australia. The outcome-anonymised reports from the SSDER provide an interactive visual summary of each patient’s treatment journey, which a practitioner can share with their patient2. New research collaborations informed by patient experience, such as the SSDER, will provide valuable real-world evidence which can offer recommendations for DED diagnosis, management and outcomes monitoring.

Clinician access to Save Sight Registry

Clinicians can use the registry, without cost, to monitor their practice outcomes, although prior ethics approval is required. In Australia, all private sites (ie. private clinics/practices) are covered by an overarching ethics approval issued by RANZCO (Ref. 09/73 and 50.14). Sites outside Australia must first obtain ethics approval from the relevant local authority. Such application will be supported by the Australian ethics approval issued by RANZCO.

To find out more please contact us at ssi.ssr@sydney.edu.au and to join or learn more about the registry, visit: https://savesightregistries.org/fight-corneal-blindness/ or scan the QR code.

Financial disclosure - The establishment of the Save Sight Dry Eye Registry was supported by unrestricted educational grants from Novartis and Seqirus.

References

- Khoo P, Downie LE, Stapleton F, et al. Clinical registries in dry eye disease: a systematic review. Cornea. 2022;41(12):1572-1583.

- Watson SL, Chidi-Egboka NC, Khoo P, et al. Efficient capture of dry eye data from the real world: The Save Sight Dry Eye Registry. AJO International. 2024;1(3):100065.

- Tan JCK, Ferdi AC, Gillies MC, Watson SL. Clinical registries in ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2019;126(5):655-662.

- Ferdi AC, Kandel H, Nguyen V, et al. Five‐year corneal cross‐linking outcomes: A Save Sight Keratoconus Registry Study. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2023;51(1):9-18.

- Mathewson PA, Williams GP, Watson SL, et al. Defining ocular surface disease activity and damage indices by an international Delphi consultation. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(1):97-111.

- Wolffsohn JS, Arita R, Chalmers R, et al. TFOS DEWS II Diagnostic Methodology report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(3):539-574.

- Hovanesian JA, Nichols KK, Jackson M, et al. Real-World Experience with Lifitegrast Ophthalmic Solution (Xiidra) in the US and Canada: Retrospective Study of Patient Characteristics, Treatment Patterns, and Clinical Effectiveness in 600 Patients with Dry Eye Disease. Clin Ophthalmol. 2021;15:1041-1054.

Dr Ngozi Chidi-Egboka is a post-doctoral researcher and clinical trial coordinator/sub-investigator for the Corneal Research Group at Sydney Medical School, the University of Sydney. Her clinical practice, teaching, research, community service and leadership activities focus on improving the delivery of anterior eye health clinical care, with a key interest in ocular surface and dry eye disease.

Professor Stephanie Watson is head of ophthalmology and the Corneal Research Group, Sydney Medical School, the University of Sydney. She is also head of Sydney Eye Hospital’s Corneal Unit, chair of Australian Vision Research, secretary of Asia Pacific Ophthalmic Trauma Society and vice-chair of RANZCO NSW Branch.