The evolution of cataract surgery since Ridley’s first IOL

The earliest forms of surgical techniques were almost certainly related to trauma and injury; indeed, evidence of drilling into the skull (trephination) has been found dating back to 6500 BCE1. Couching, the earliest form of cataract surgery – whereby a sharp needle is pushed through the limbus to dislodge a mature cataract into the vitreous – was first described by India’s Sushruta (circa 800 BCE), who is considered the father of surgery.

Although couching continues to this day in parts of the world2, the next major change did not occur until the 18th Century. Jacques Daviel (1696–1762), surgeon and oculist to Louis XV of France, performed the first extracapsular extraction (ECCE) on 8 April 1747, in Cologne (Fig 1). The inferior incision was created with a triangular blade and curved scissors and the nucleus expressed with the thumb or a spatula, with little attention paid to the cortex. This technique continued with modest changes for 200 years, albeit with reports of Italy’s Felice Tadini and Johan Casaamata inserting glass beads after surgery which, of course, dropped into the vitreous. Aphakic glasses (typically +10D or more) restored vision post-ECCE but the residual cortex after nucleus expression caused recurring visual loss from cortical fibrosis or Soemmering rings (described by Detmar Soemmering in 1828) and Elschnig pearls. Numerous further surgeries were required to clear the visual axis.

Fig 1. Daviel’s ECCE technique. The patient was seated in front of him

The development of intracapsular cataract extraction (ICCE), which entails also removing the capsule, has been attributed to Samuel Sharp (1709–1778) from Guy’s Hospital, London. His first paper was published in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society in 17533. His detailed biography includes quotes from his own writings explaining how he used a thin blade (like the von Graefe knife of 1850) to open the eye in one movement and express the lens from below4. Unlike his contemporary, Jaques Daviel, he appreciated the benefit of removing the capsule with the cataract.

Barcelona’s Hermenegildo Arruga (1886–1970) is most famous as a retinal surgeon. However, he also invented the Arruga forceps in the early 20th century, for grasping the anterior lens capsule and removing the lens in toto, thereby avoiding cortical issues to provide better clarity of vision (Fig 2). In the same city, Ignacio Barraquer invented the erysophake in 1917, a suction device to latch onto the anterior capsule in a less traumatic fashion, to achieve intracapsular extraction. Subsequently, Tadeusz Krwawicz of Poland introduced a freezing tip (cryoprobe) to adhere to the capsule and perform an ICCE in 1961. Alpha chymotrypsin was introduced by Joaquin Barraquer in 1957 to dissolve the zonules and facilitate the removal of the lens without rupturing the capsule. When combined with cryo surgery, the zenith of ICCE techniques had been achieved.

Fig 2. ICCE using Arruga forceps, removing the lens intact

However, patients were still aphakic, with all the inherent disadvantages of 30% magnification of images in glasses, weight of thick spectacle lenses, reduced visual fields and, of course, extremely poor vision without glasses. However, ICCE surgery persisted until the late 1970s during the nascent intraocular lens development.

Cataract and Mouse

In 1940, during World War II’s Battle of Britain, many fighter pilots sustained severe eye injuries from pieces of shattered plane canopies, which were made of poly-methyl-methacrylate (PMMA). One such pilot was Gordon ‘Mouse’ Cleaver of 601 Squadron. He was blinded in his right eye and retained numerous PMMA pieces in his left eye, requiring surgery. He was reviewed by Dr Sir Harold Ridley, consultant ophthalmologist at Moorfields Eye Hospital and St Thomas’ London (Fig 3), who noted how inert the PMMA was in Mouse and other pilots’ eyes. In 1948, medical student Stephen Perry, observing Sir Harold doing an ICCE, asked why a lens wasn’t inserted to replace the one removed. Sir Harold, who had been mulling over this concept for some years, now had the courage to proceed and asked Rayner & Keeler Ltd (London) to make a lens of PMMA similar to the crystalline lens. The first case (ECCE) was undertaken in November 1949 at St Thomas’ Hospital rather than Moorfields, where the controversial surgery would have attracted too much attention. The first lenses were based on Gullstrand’s schematic eye, but with the refractive index being wrong, the first two cases ended up very myopic (Fig 4).

Fig 3. Ridley inserting his fifth lens. Note the very early use of corneal sutures

However, the cat was soon out of the bag when one post-operative patient went to Harley St and saw Dr Frederick Ridley (also an ophthalmologist, but no relation) instead of Sir Harold Ridley! Sir Harold gave his first public lecture (with two patients to view) on his new operation at the Oxford Ophthalmological conference in July 1951, but drew much opprobrium from most of his colleagues. Sir Stewart Duke-Elder, the era’s doyen of British ophthalmology, refused to see the patients and never spoke to Sir Harold again – perhaps because he had seen Cleaver in clinic in 1940 and not thought of the idea. One common criticism was that Sir Harold had not done any experiments beforehand. This is not strictly correct, since Cleaver and others with intraocular PMMA fragments, had served as subjects of a pre-clinical study of an invention that had not yet been invented. Despite the vilification, Sir Harold’s supporters included Professor Peter Choyce (UK) and Drs Svyatoslav Fyodorov (Russia), Edward Epstein (South Africa), Cornelius Binkhorst (Netherlands), Warren Reese (US) and numerous others, many of whom went on to make major contributions to intraocular lens (IOL) development.

Fig 4. A Kelman multiflex style, anterior chamber, angle-supported, IOL

Sir Harold’s operation did not gain much initial popularity because of the extra-capsular technique and cortex problems. Also, with poor fixation of the implant there was inferior decentration. But at this stage, surgeons knew implants were more acceptable so ICCE and anterior-chamber (AC) lenses became more common.

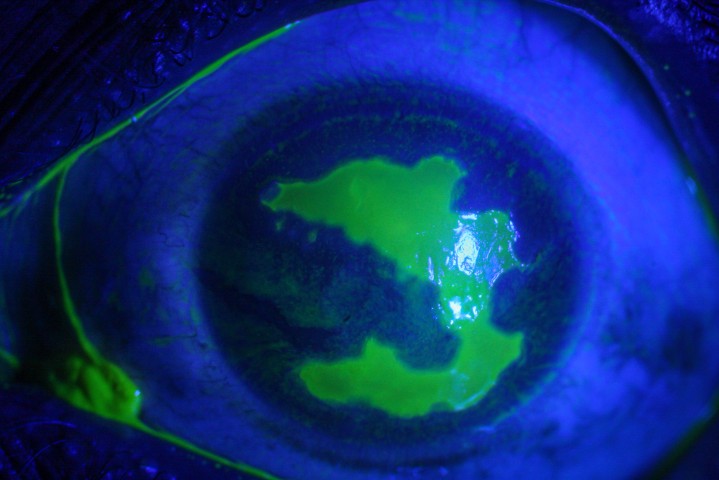

This brought more, new, complications. Although the lens material was the same as Sir Harold’s, poor manufacturing quality and anterior chamber diameter sizing issues led to many cases of endothelial decompensation and what later became known as UGH (uveitis glaucoma haemorrhage) syndrome. Many eyes were lost. As a result, New Zealand ophthalmologists trained in the UK in the ‘50s and ‘60s came back very disillusioned with the idea of IOLs and uptake was slow. After many iterations of AC IOLs there remains only one, the Kelman Multiflex (Fig 5), which has stood the test of time.

Fig 5. A Binkhorst irido-capsular IOL following IC lens extraction

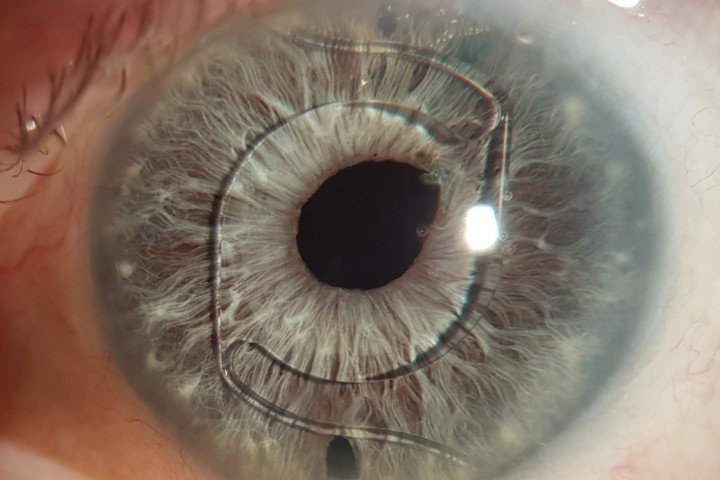

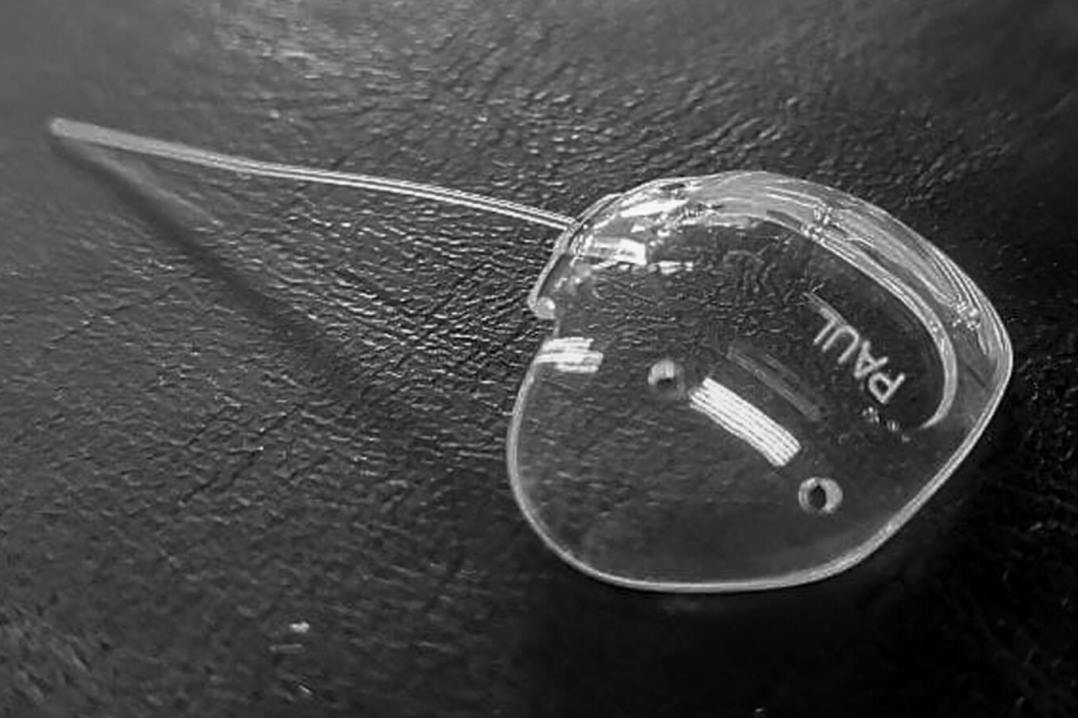

Dr Binkhorst (1912–1995) subsequently improved AC implant fixation. Initially, following an ICCE, he devised a lens design using loops (haptics) either side of the iris, with the optic lying on the anterior surface of the iris (Fig 6). Later, he refined ECCE by removing all the cortex by means of a manual suction technique. The optic was still on the front of the iris but the haptics were sitting on the posterior capsule and within some form of capsule bag (Fig 7). Honouring this advance and others is the prestigious eponymous lecture at the American Society of Cataract and Refractive Society (ASCRS) annual meeting.

Fig 6. Iris clip IOL in an eye that developed pseudophakic bullous keratopathy and required a penetrating keratoplasty

The next evolution was a complete about-turn from Sir Harold’s original posterior-chamber style of lenses. But its success would have to await Gimbel and Neuhann’s development of continuous curvilinear capsulorhexis, which retains the lens within the capsule and ensures its centration5. Dr Steven Shearing (US) 1997 devised the first three-piece posterior chamber IOL (PCIOL) with a PMMA optic and flexible polypropylene loops which ensured centration within the bag6. In the UK, Dr John Pearce introduced a one-piece haptic PMMA lens for in-the-bag insertion7. From here, many design variations ensued but the principle was set and Sir Harold’s first idea vindicated. Just one problem remained: the lens was a non-flexible 6mm optic PMMA haptic which required a large wound incision and sutures, which resulted in induced astigmatism, among other disadvantages.

Fig 7. A trifocal IOL in situ showing a diffractive lens pattern

Phacoemulsification breaks up the cataract with ultrasonic pulses and is done through a 2–3mm incision. It was invented in 1967 by Dr Charles Kelman but did not become mainstream until the early 1990s. This opened the door for foldable implants, the first being silicone lenses in 1985, followed by acrylic one from 1993, which could be injected through the small phaco incision. The material is still used today and has the advantages of less astigmatism, better vision and less trauma and infection risk. Development of lenses from here included toric lenses from 19948 and multifocal-style lenses9 (mfIOL), initially from 1987 on a PMMA platform. However, interest did not take off until they became available in a foldable form in 199210 and have since evolved along the lines of many different optical principles (Fig 8).

In New Zealand, Dr Grant Johnston implanted the first IOL in Hamilton in the early ‘70s. Subsequently, Dr Calvin Ring gave a paper on his experiences to New Zealand ophthalmologists in 1978 but was professionally ostracised, particularly in the South Island11. Since then, younger New Zealand ophthalmologists have led the way, staying at the forefront of IOL developments.

References

1. Restak R (2000) Mysteries of the mind. National Geographic Society, Washington, DC

2. Gilbert C.E., Murthy, G.V.S., Sivasubramaniam S., Kyari F., Imam A., Rabiu M.M., Abdull M., Tafida, A. “Couching in Nigeria: Prevalence, Risk Factors and Visual Acuity Outcomes.” Ophthalmic Epidemiology. 17.5 (2010): 269-275.

3. Phil. Tr. Lond. 1753. Xlviii, pt. 1. 327

4. Samuel Sharp, the first surgeon to make the corneal incision in cataract extraction with a single knife: a biographical and historical sketch / by Alvin A. Hubbell, M.D., Ph.D., Clinical Professor of Ophthalmology, University of Buffalo.Hubbell, Alvin A. (Alvin Allace), 1846-1911

5. Gimbel, HV; Neuhann, T. (January 1991). "Continuous curvilinear capsulorhexis". J Cataract Refract Surg. 17 (1): 110–1.

6. Shearing SF: The 1986 Innovator's Lecture. Resurrection of posterior chamber lenses or why innovation occurs when it does. J Cataract Refract Surg 12:66.669, 1986

7. Pearce, J.L Sixteen months experience with 140 posterior chamber intraocular lens implants Br J Ophthalmol. 1977; 61:310-315

8. Shimizu K, Misawa A, Suzuki Y. Toric intraocular lenses: correcting astigmatism while controlling axis shift. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1994 Sep;20(5):523-6. [PubMed]

9. RH Keates, JL Pearce, RT Schneider Clinical results of the multifocal lens. J Cataract Refract Surg, 13 (1987), pp. 557-560

10. RF Steinert et al. A prospective, randomized, double-masked comparison of a zonal-progressive multifocal intraocular lens and a monofocal intraocular lens Ophthalmology (1992

11. Eye surgeons and surgery in New Zealand Bruce Hadden. Published by Wairau Press, Random House, 2012. ISBN 9781927158036. Page 94

Dr Peter Ring studied Ophthalmology at Moorfields Eye Hospital in London and during this time did two courses with Dr Binkhorst in Holland and assisted Harold Ridley on two occasions. He returned to New Zealand and opened Eye Institute with Drs Bruce Hadden and Tony Morris in 1995.His interests are refractive and anterior segment surgery and oculoplastics.