Let nature take care of it

Non-melanoma skin cancers (NMSCs) are the commonest cancers in Australia and New Zealand. In 2006, the age-standardised incidence of NMSCs was 406 per 100,000 population in New Zealand1. Treatment of NMSCs represents a significant cost to Australasian healthcare systems1,2 and their incidence is rising. The two commonest NMSCs are basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) and squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs). Between 5% and 10% of NMSCs occur in the periocular region, accounting for more than 90% of all ophthalmic tumours3. The lower lid is the commonest location for these lesions.

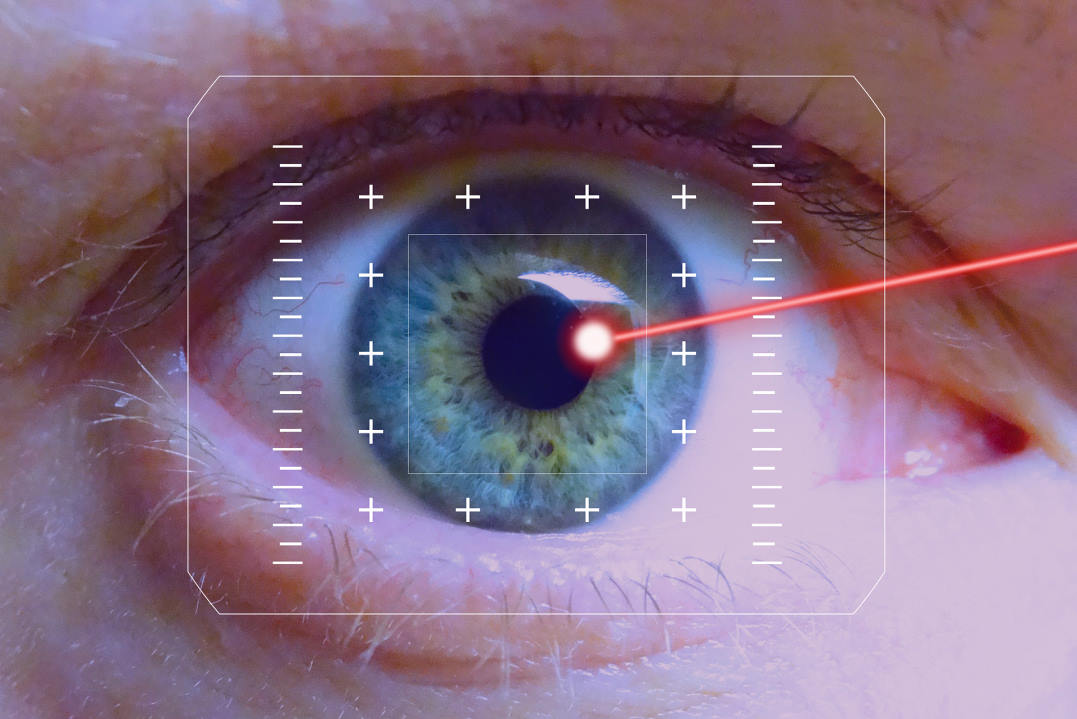

The first-line treatment for NMSCs is surgical excision. Commonly, 2-4mm of normal-appearing tissue around the tumour is removed. Following excision, the specimen undergoes histopathological analysis to confirm the type of cancer and whether all the tumour cells have been removed.

To preserve visual function, minimising excision of eyelid tissues is crucial. Surgical excision with histological margin control is used to reduce the removal of uninvolved surrounding tissue and increase the rate of tumour clearance. Depending on the available local expertise, various techniques of margin control are employed. These include histological frozen section, rapid paraffin section analysis and Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS). For primary BCCs and recurrent BCCs, MMS has the highest five-year cure rates of 99% and 96%, respectively4.

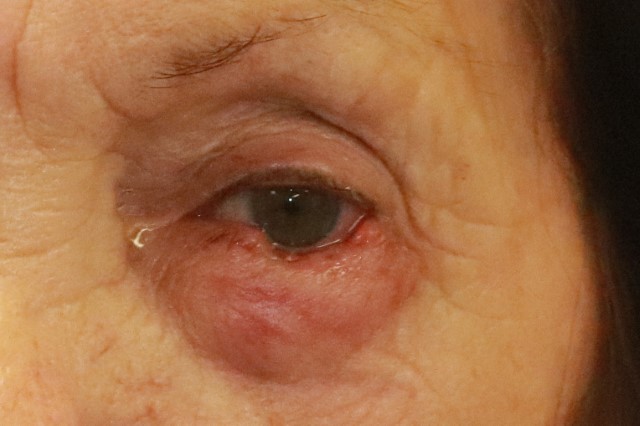

After tumour excision, the defect is usually reconstructed. The aim of lid reconstruction is to restore the function of the eyelids to maintain vision. Direct (primary) closure (DC) is the commonest technique in lower lid reconstruction (Fig 1). It can be performed rapidly and yields good results. In particular, it can give excellent alignment of the cut edges of the lid margin. If lid margin alignment is not achieved, tear film disturbance, trichiasis, notching and poor cosmesis can occur. If the lid is directly closed under undue tension, entropion, wound dehiscence (reported in another study in 7.4% of cases5) and corneal injury can occur.

Fig 1. Left: patient with a left lower lid BCC; middle: excision of lesion and remaining full-thickness defect; right: direct (primary) closure of defect

For reconstructing full-thickness lower-lid defects that cannot be closed directly, many techniques have been described. The Hughes flap – a tarsoconjunctival-advancement flap (Fig 2) – is commonly used and can achieve excellent results. The disadvantage is that the eye is sutured closed for at least five days. A second operation is required to divide the flap and re-open the eye. Therefore, it cannot be used for patients with poor vision in the contralateral eye6.

Fig 2. Hughes flap procedure. The posterior lamella of the lower lid defect is filled by an attached flap of conjunctiva and tarsal plate brought down from the ipsilateral upper eyelid. The anterior lamella is then replaced by advancing a local skin flap or placing a free skin graft over the posterior lamella

The hands-off approach

Another option for reconstruction is laissez-faire (LF), a French term meaning ‘leave it alone’. It utilises secondary intention healing (SIH), the natural wound healing process. Its use in the eyelids was first reported by Brown and Fryer in 1957 after their patient had a lower lid invasive BCC excised. Reconstruction was delayed due to their concern about local recurrence. Over the next few weeks, the defect healed itself satisfactorily and reconstruction was not required.

When used in the eyelids, LF is better suited to the lower lid, which has a less crucial role in protecting the cornea. A small number of investigators have reported the use of LF to treat full-thickness lower lid margin defects7–10. Mehta published the first case series of 11 patients demonstrating successful application of LF7, describing defects involving up to half of the horizontal width of the lid achieving near-normal cosmesis. Morton described similar good results with LF in his prospective case series of 34 patients8.

Various size defects involving the lid margin can be treated with LF7,9. The final functional and aesthetic outcomes of LF in the lower lid can be excellent and, compared to other forms of surgical reconstruction, it has the advantages of simplicity, ease of wound care, no donor site morbidity, no suture complications and reduced cost and surgical time7–10.

SIH of the lower lid takes 2-6 weeks to complete7,10. Due to the longer healing time, LF may be an unpopular choice for some patients. Previous studies have reported low rates of trichiasis, loss of eyelashes, notching, retraction and ectropion secondary to wound contracture from LF7–10. These are possible complications that may also arise when reconstructing the lower lid using the DC method.

Study of laissez-faire healing

To investigate the role of LF in full-thickness lower lid healing and to compare it to DC, we undertook a randomised controlled trial. The study was based in the oculoplastic service at Waikato Hospital, New Zealand. Patients who had undergone excision of lower lid tumours, provided the resulting defect could be directly closed, were randomly assigned to either LF or DC. The study analysed functional and aesthetic outcomes and assessed patient satisfaction. Since DC can achieve excellent results, the null hypothesis of the study was that LF does not demonstrate inferiority to DC.

Fig 4. A 32-year-old female patient with a right lower lid BCC. In order from the top: pre-operative; LF at day 5; LF at 3 weeks; LF at 3 months

The LF technique has been well accepted by all patients. When introducing the study, many patients indicated that they had already thought ‘leaving it to heal itself’ would be a good option, if possible. This was contrary to our expectation that patients would favour surgical repair.

Preliminary results from the first 30 patients demonstrated very satisfactory results in both LF and DC groups, with comparable functional results, aesthetic outcomes and patient satisfaction. The overall satisfaction and self-evaluated final cosmetic outcome scores were greater than nine out of 10 for each group.

Low rates of corneal superficial punctate keratopathy (SPK) and trichiasis were observed in both the LF and DC groups. With the use of ocular lubricants in the study patients, SPK resolved completely by the three-month follow-up visit. Wound dehiscence occurred in two of the DC patients. Both cases then went on to heal satisfactorily with LF. No cases have required revision surgery.

Fig 5. An 86-year-old male patient with a right lower lid infiltrating BCC. In order from the top: 1 day after MMS; LF at day 5; LF at 3 weeks; LF at 3 months

Patients with lower lid tumours commonly underwent tumour excision using MMS, performed by dermatological surgeons at another site. The wound was dressed overnight and reconstruction was scheduled for the following day. It is worth noting that due to wound contracture, the size of the lower lid defect often became measurably smaller overnight (Fig 3). Thus, delaying reconstruction by a day or more may be worth considering in certain patients since the size of the defect influences the surgeon’s choice of reconstructive method. When the defect spontaneously becomes smaller, LF can declare itself as a more obvious option.

Fig 3. Left: left lower lid defect immediately after MMS; right: same defect the next day

Early results from our trial are very encouraging and support the use of LF for managing full-thickness lower lid margin defects. The final results from the trial will be useful for surgeons to decide between LF and DC in the future with the potential to allow nature to take a greater role in lid reconstruction.

This study obtained ethics approval from the Health and Disability Ethics Committees. Photos in this article have been used with patients’ permission.

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge my supervisors Dr Stephen Ng and Dr James McKelvie, from Waikato Hospital and the University of Auckland, and Dr Jie Zhang, senior research fellow from the University of Auckland’s Department of Ophthalmology.

References

4. Nouri, K. Mohs Micrographic Surgery. (Springer Science & Business Media, 2012).

7. Mehta, H. K. Spontaneous reformation of lower eyelid. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 65, 202–208 (1981).

Dr Sarah (Jee Ah) Oh is an ophthalmology registrar (non-training) at Tairāwhiti District Health Board and an MD candidate in the University of Auckland’s Department of Ophthalmology. Her research focuses on periorbital cutaneous malignancy and reconstruction.