Where have all the men gone?

You probably wouldn’t give this blurry 1986 photo of third-year University of Auckland optometry students a second glance.

There’s nothing particularly notable about it, other than maybe a bit more volume in the hair, the lack of laptops, the quaint ring binders and even quainter pencil cases. But these future optometrists unknowingly faced huge changes ahead – the struggle to be recognised as a profession, and as professionals; the fight to maintain control of refraction and contact lens prescribing and gain diagnostic endorsement; the recognition of optometry’s responsibility to Te Tiriti o Waitangi; the rise of non-optometrist ownership of practices and corporatisation; and the battle for therapeutic accreditation to allow them to do what they’d been trained to do.

But that was to come.

What’s most significant about this photo, at this time, is the number of females in it. This optometry class was the university’s first to have females in the majority. The proportion of women had been increasing since the degree programme started, but 1985’s second year had 77% females, which was pretty noticeable in a class of just 13.

The profession’s response was one of concern for the workforce, since optometrists, particularly in the provinces, were in short supply. How many of these students would get pregnant and drop out? How many would be prepared to leave their boyfriends to work in far-flung corners of New Zealand? How many would stop practising once they were married…?

The glass ceiling

In 1984, playwright and University of Auckland drama lecturer Mervyn Thompson was beaten and tied to a tree by a group of six (still) anonymous women who were tired of his alleged abusive behaviour. In this post-#MeToo era it’s hard to believe that in early 1980s New Zealand marital rape was not illegal, the concept of a power imbalance in the work or education space was unrecognised and sexual harassment in the workplace was common and unacknowledged.

When the School of Optometry’s then head vowed to make us cry before we graduated, we just shrugged, knowing he was more scared of us that we were of him. We were empowered! Our perception was that all men were potential rapists, while women had Adrienne Winkelmann power suits to wear and glass ceilings to break.

The young women in this photo learned to navigate the 1980s New Zealand optometry scene. Some realised that subtle flirting could get you higher marks in practical exams; some learned that wearing shorter skirts and make-up to an interview bagged the job. Some saw that older female optometrists regarded us as competitors, when we so desperately needed mentors. Most learned to bat off sexist comments from patients who had no filter, and we all learnt that many middle-aged male optometry colleagues had scary, Cazal-wearing wives who were suspicious of us.

A gender about-turn

When we graduated, the optometry profession was overwhelmingly male. It wasn’t until 2014 that more practitioners in Australia identified as female than male. In the 2023 Optometrists and Dispensing Opticians Board (ODOB) workforce survey, 61.3% of New Zealand’s optometrists identified as female.

So, why are more women entering optometry?

The profession is in demand, fulfilling and flexible. If you live outside Auckland, it’s not too difficult to find employment and, to a certain extent, dictate your hours. Unlike law or medicine, long working days and weeks are not the norm. Overwhelmingly, women want to balance work and family with the option of extended breaks.

It’s a tedious fact that women still face workplace barriers: to promotion, training, equal pay and partnership. Part-time work requires increased time-management skills (there’s nothing like an extra charge on the after-school care bill to keep you punctual) and a return to the workplace after maternity leave brings increased joy for your job, improved understanding of your patients and the opportunity to go to the toilet by yourself!

In a nutshell, our profession is generally kind to women – I’ve faced far fewer barriers than my female ophthalmology colleagues have.

A feminist future?

This digital age and our use of social media has led to a tribal or more binary way of thinking. F. Scott Fitzgerald said it best when he wrote: “The test of first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposing ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function.” Can you hold the desire to be an independent career woman who has it all, alongside the desire to be a trophy wife? Can you get behind the ‘sisters before misters’ mantra but call a woman who stands up for herself bossy?

Not surprisingly, I discovered that not all male optoms are bastards and the overwhelming majority are caring, generous with their knowledge and feminist in their thinking. Many were also relentless in fighting, politically, for the profession.

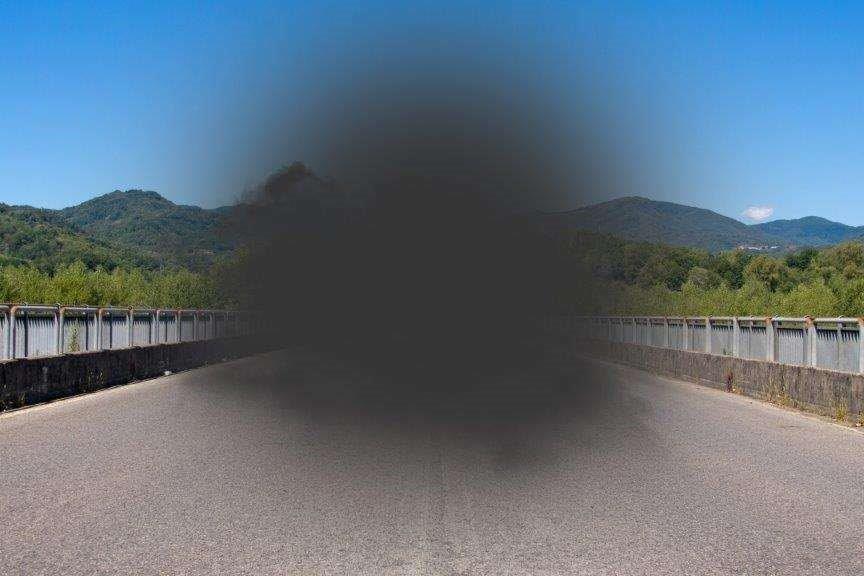

A certain dissonance occurs, at least for me, when I ask myself what effect a predominantly female and part-time workforce has on the profession. Is it actually a good thing? Or, to misquote Peter, Paul and Mary, where have all the males gone? Predominantly female professions are given lip service and are generally undervalued, particularly when non-unionised. Let’s not forget the praise heaped on the nursing and teaching professions during the Covid lockdowns, only for both to be subsequently forced to fight to gain better financial recognition for their skills. I wonder if optometry, with its mainly female, part-time and employed workforce, is heading the same way? Do we need to have skin in the game to determine our own fate?

With their less risk-averse nature, males are perhaps more inclined to own a business, which more often requires a full-time commitment. But are males less attracted to this profession because of the perceived (or not) difficulties in owning your own practice? Do we, in fact, now need more male optometrists to enable the profession to practise in a more diverse manner and to challenge the state of optometry?

Before anyone points out the hypocrisy of me asking these questions, please refer to the words of Mr Fitzgerald above.

Carrying the lion’s share of the profession comes with the responsibility of continuing the good fight for its future. That means female optoms need to continue to push politically to maintain our position as primary care eye practitioners and to resist forces within our workplace that tamper with our autonomy and ethics. (Thank you, NZAO council.)

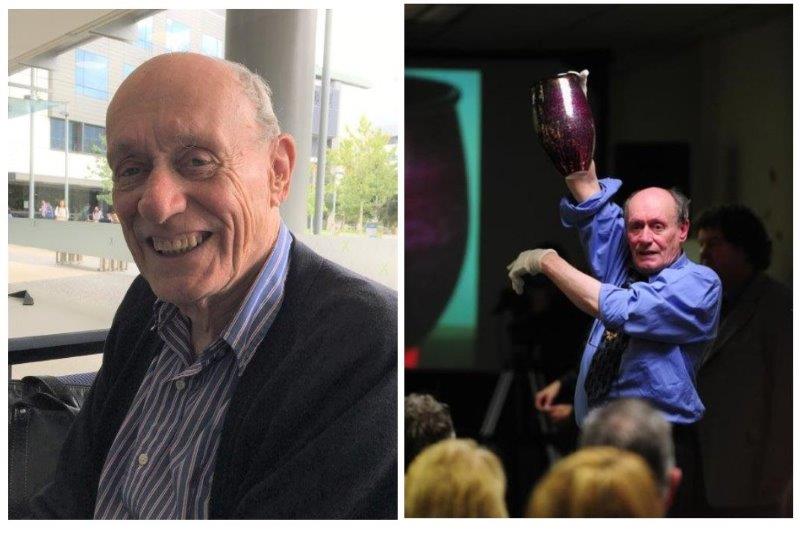

Optometry has advanced dramatically since this photo was taken because of those males and females who went before us – we are practising on the shoulders of giants.

And, in case you’re wondering, every feisty female in my cohort graduated. There were no tears or pregnancies, but there was a change in the head of department!

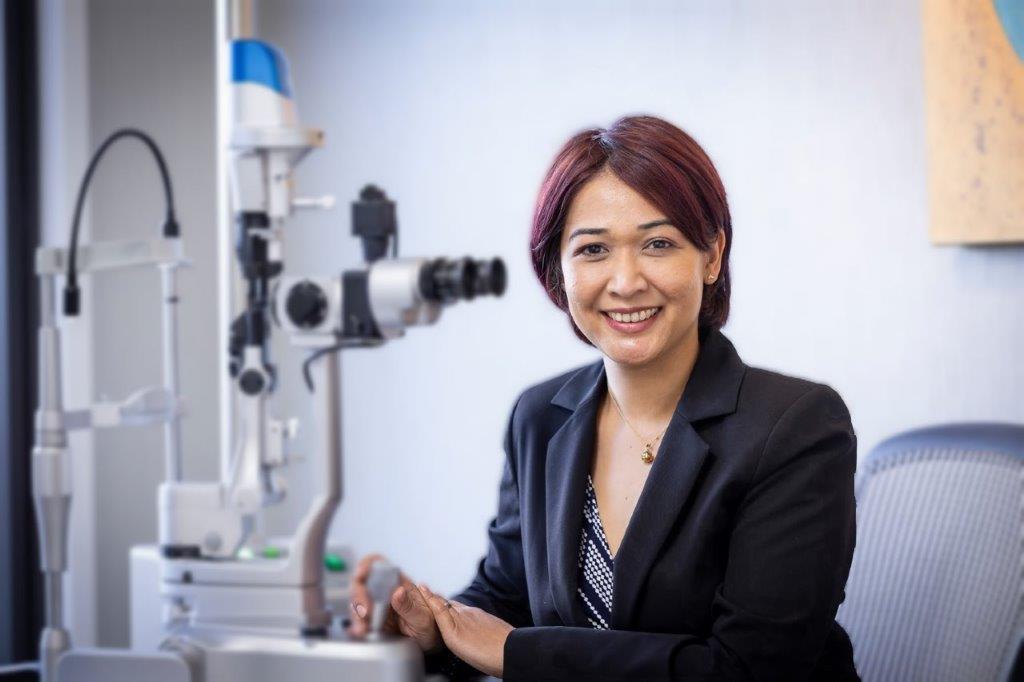

A therapeutically qualified optometrist in Christchurch, Catherine Small returned to Auckland Uni in 2003 as one of the first therapeutic trainees after the new scope of practice was approved, taking her final oral exam while eight months pregnant (and continues to practise)!